Tag: TIF

-

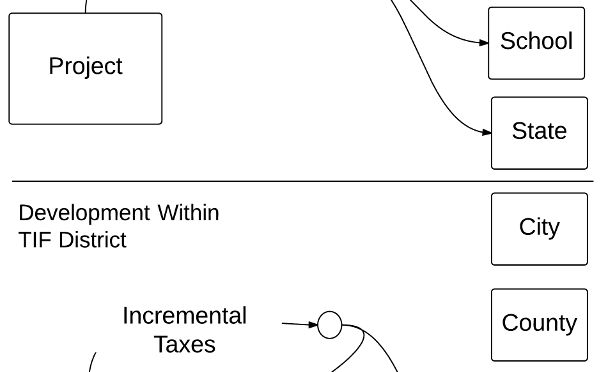

Tax increment financing (TIF) resources

Resources on tax increment financing (TIF) districts.

-

Wichita TIF projects: some background

Tax increment financing disrupts the usual flow of tax dollars, routing funds away from cash-strapped cities, counties, and schools back to the TIF-financed development. TIF creates distortions in the way cities develop, and researchers find that the use of TIF means lower economic growth.

-

Economic development in Wichita: Looking beyond the immediate

Decisions on economic development initiatives in Wichita are made based on “stage one” thinking, failing to look beyond what is immediate and obvious.

-

Wichita economic development items

The Wichita city council has been busy with economic development items, and more are upcoming.

-

City of Wichita State Legislative Agenda: Economic Development

The City of Wichita wishes to preserve the many economic development incentives it has at its disposal.

-

Union Station development drains taxes from important needs

The diversion of future property tax revenues away from local governmental treasuries should concern every taxpaying citizen when one considers the many needs for these funds, says John Todd.

-

Errors in Wichita Union Station development proposal

Documents the Wichita City Council will use to evaluate a development proposal contain material errors. Despite the city being aware of the errors for more than one month, they have not been corrected.

-

Union Station TIF provides lessons for Wichita voters

A proposed downtown Wichita development deserves more scrutiny than it has received, as it provides a window into the city’s economic development practice that voters should peek through as they consider voting for the Wichita sales tax.

-

What incentives can Wichita offer?

Wichita government leaders complain that Wichita can’t compete in economic development with other cities and states because the budget for incentives is too small. But when making this argument, these officials don’t include all incentives that are available.

-

Kansas budgeting “off the tops” is bad policy

Direct transfers of taxpayer money sent to a specific business or industry is always a tough sell to politicians, let alone the voting public. But, that is why some corporations pay lots of money to lobbyists, writes Steve Anderson for Kansas Policy Institute.

-

Sedgwick County economic development incentives 2013 status report

Sedgwick County economic development incentives 2013 status report

-

Wichita TIF history and performance report

Wichita TIF history and performance Report, 2011. Prepared by Department of Finance and Office of Urban Development, City of Wichita.