Tag: Downtown Wichita revitalization

-

Update: Wichita city sales tax not passed

There was no successful Wichita city sales tax election. City documents were mistaken, which raises more issues.

-

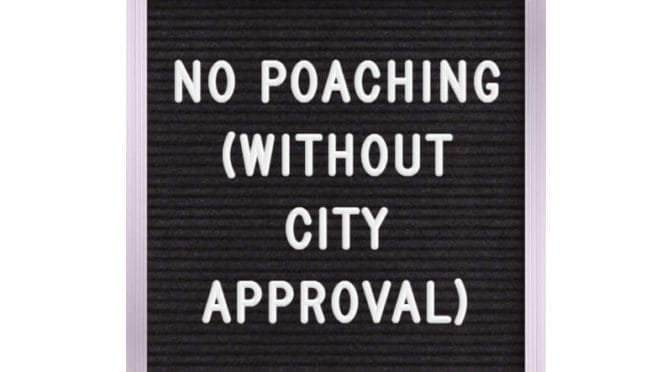

In Wichita, no tenant poaching, unless waived

The city of Wichita has included anti-poaching clauses in development agreements to protect non-subsidized landlords, but the agreements are without teeth.

-

Slow down on Wichita ballpark land deal

A surprise deal that has been withheld from citizens will be considered by the Wichita City Council this week.

-

Another Wichita survey, another set of problems

The Wichita Eagle editorial board notices problems with a survey gathering feedback on Century II.

-

Naftzger Park costs up, yet again

The cost of fixing an oversight in the design of Naftzger Park in downtown Wichita is rising, and again we’re not to talk about it, even though there are troubling aspects.

-

Facade improvement program raises issues in Wichita

An incentive program in Wichita should cause us to question why investment in Wichita is not feasible without subsidy.

-

Naftzger Park cost rising, and we’re not to talk about it

The cost of the Naftzger Park makeover is rising, will be paid for with borrowed funds, and possibly handled without public discussion.

-

More TIF spending in Wichita

The Wichita City Council will consider approval of a redevelopment plan in a tax increment financing (TIF) district.

-

Wichita Wingnuts settlement: There are questions

It may be very expensive for the City of Wichita to terminate its agreement with the Wichita Wingnuts baseball club, and there are questions.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Sedgwick County and Wichita issues

The end of a Sedgwick County Commission election, the *Wichita Eagle* editorializes on school spending and more taxes, and Wichita Mayor Jeff Longwell seems misinformed on the Wichita economy.

-

Wichita Eagle calls for a responsible plan for higher taxes

A Wichita Eagle editorial argues for higher property taxes to help the city grow.

-

Project Wichita survey

The Project Wichita survey is about to end. Will it have collected useful data?