Tag: Downtown Wichita revitalization

-

Should Wichitans care when ballpark development starts?

This article discusses the financial implications of the delayed development around Riverfront Stadium in Wichita.

-

Downtown Wichita Business Activity

Business activity in downtown Wichita continues to rise.

-

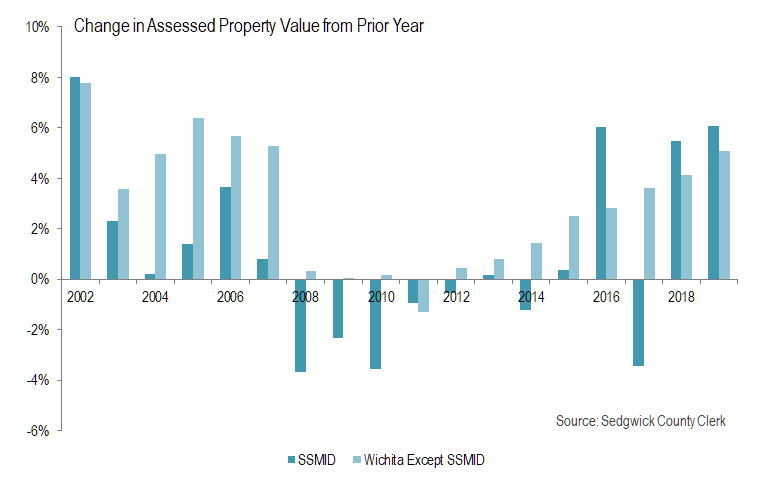

Downtown Wichita Tax Base

There’s been much investment in downtown Wichita. But it isn’t evident in the assessed value of property, although the recent trend is positive.

-

Naftzger Park event management agreement still ambiguous

This week the Wichita City Council will update an agreement from last year, but it appears important issues were not addressed.

-

Downtown Wichita jobs rise

The reported number of jobs in Downtown Wichita rose in 2018, but there is an issue with the data.

-

Downtown Wichita population is up

New Census Bureau data shows the population growing in downtown Wichita.

-

Downtown Wichita attraction attendance

Attendance at downtown Wichita attractions presented in an interactive visualization.

-

Intrust Bank Arena loss for 2019 nears $5 million

A truthful accounting of the finances of Intrust Bank Arena in downtown Wichita shows a large loss.

-

Rethinking the city and the community for a post-pandemic world

How has the pandemic affected cities in general and Wichita specifically, and what are implications for the future?

-

Naftzger Park on the web: Do we care?

A badly outdated portion of Wichita’s website makes me wonder: Does anyone care?

-

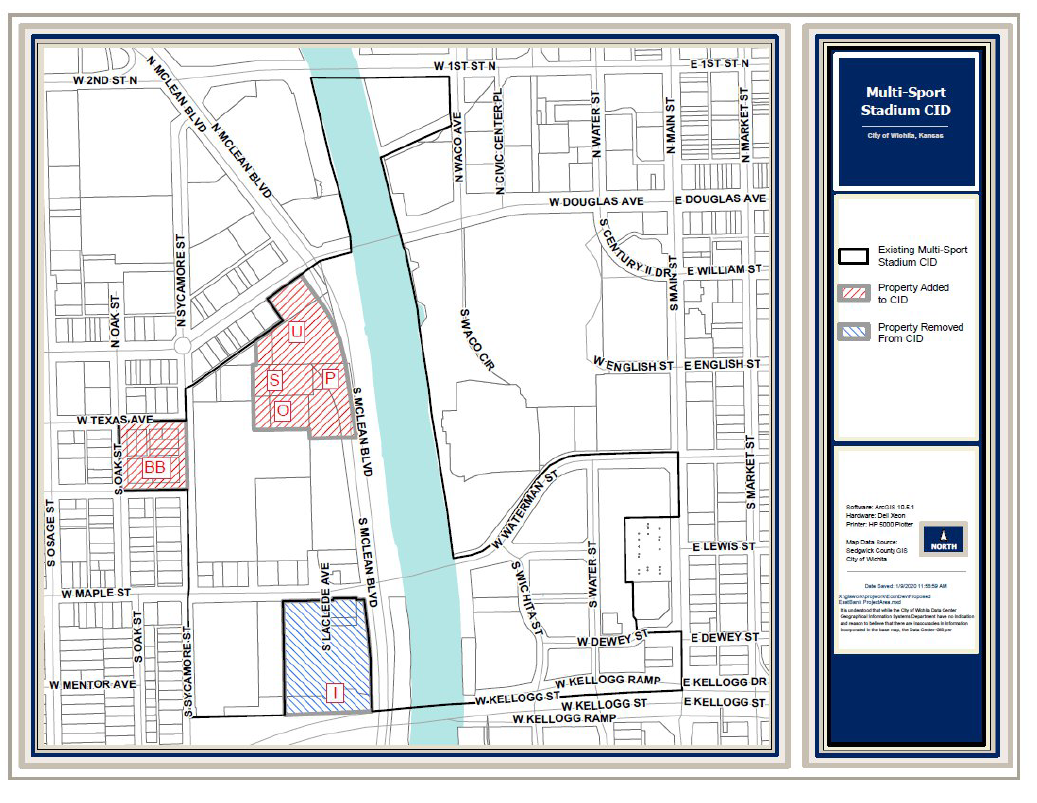

Wichita taxing district to expand

The City of Wichita plans to expand a special tax district.

-

Naftzger Park event management agreement ambiguous

The profit-sharing agreement for Naftzger Park event management contains ambiguity that could lead to disputes.