A Wichita City Council member sets out to correct misinformation, but instead makes a number of factual errors.

At last week’s Wichita City Council meeting, Council Member Janet Miller (district 6, north central Wichita) took an opportunity to correct misinformation she says was presented. It wasn’t the first time she’s done that; see On Wichita’s Exchange Place TIF, Janet Miller speaks, City council members on downtown Wichita revitalization, Wichita Old Town TIF district illustrates cost and harm of subsidy, Wichita fluoridation debate reveals attitudes of government, and At Wichita City Council, facts are in dispute for other examples of Miller attempting to correct misinformation.

It should be noted that Miller and some other council members make these statements from their perch on the city council bench. There, their statements can’t be questioned or rebutted except by other council members. That happens only rarely. It’s left to others to do that job.

Here are some examples from the most recent meeting, with video following.

On the positive economic impact to the city of the project, Miller said “For every dollar that the city invests in any part of this project the return to the public good is two point six two.” But as I detail in In Wichita, economic development policies are questioned, this is not true for this project when the large cost to the city’s debt service fund is considered, as has been the city’s policy for economic development incentives. Except: Apparently new policy has been formulated to suit the special needs of this project.

Also, the hotel received tax credits that were a cost to the state and the nation, of which Wichita taxpayers are part. These costs were not included in the cost-benefit study that Miller cited.

In promoting the benefit of the hotel, Miller said that the city retains one hundred percent of the guest tax collected by the hotel. She didn’t tell the audience that this wasn’t her preference. Miller voted for an ordinance that would have re-routed 75 percent of that tax back to the hotel, to be used in any way its owners want. But Kansas law allowed citizens to challenge the special type of ordinance that was used to implement this law. By gathering signatures and winning an election, this guest tax redirection that Miller supported was defeated. Now, she says that having no such redirection is a positive factor.

Miller also mentioned the retail space lease in the parking garage, saying it’s “being leased to a third party professional management entity who has the expertise to recruit high quality tenants,.” She added that this will result in increased tax revenue to the city.

This is true, I suppose. But it doesn’t negate what Miller voted to do for one of her long-time campaign supporters. She vote to build, at taxpayer expense, about 8,500 square feet of retail space in the garage. Then she voted to lease it to her campaign contributors for $1 per year. This space can then be rented out for, at minimum, about $127,500 annually. We don’t really know what the public purpose for this is, or why this had to be done. Except for cronyism — we’re sure of that.

Miller also said that as a council member she earns a salary that is 30 percent of her previous salary. Council members have a salary of around $35,000, which implies that Miller previously earned around $116,000. Good for her to have earned that.

Miller also carped about the referendum election in February 2012, noting that the “city” could not raise money and campaign for the project. That’s not entirely true. We saw that in November 2004 and November 2008, government officials campaigned “off the books” for the temporary county sales tax and Wichita school bond. Council members could have spoken as private individuals in favor of their position, whatever it was.

As it turned out, the Ambassador Hotel group spent four times as much as the side that won. Lack of money to get out a message was not a problem.

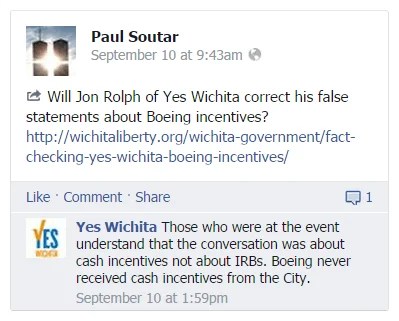

As far as misinformation during the campaign, I would ask readers to review the Wichita Eagle’s fact-checking article, as well as my own article Fact checking the Wichita Ambassador Hotel campaign. Additionally, the campaign site I created at dtwichita.com is still available, as are the articles on wichitaliberty.org. If Miller or anyone else is able to find an error, I will post a correction.