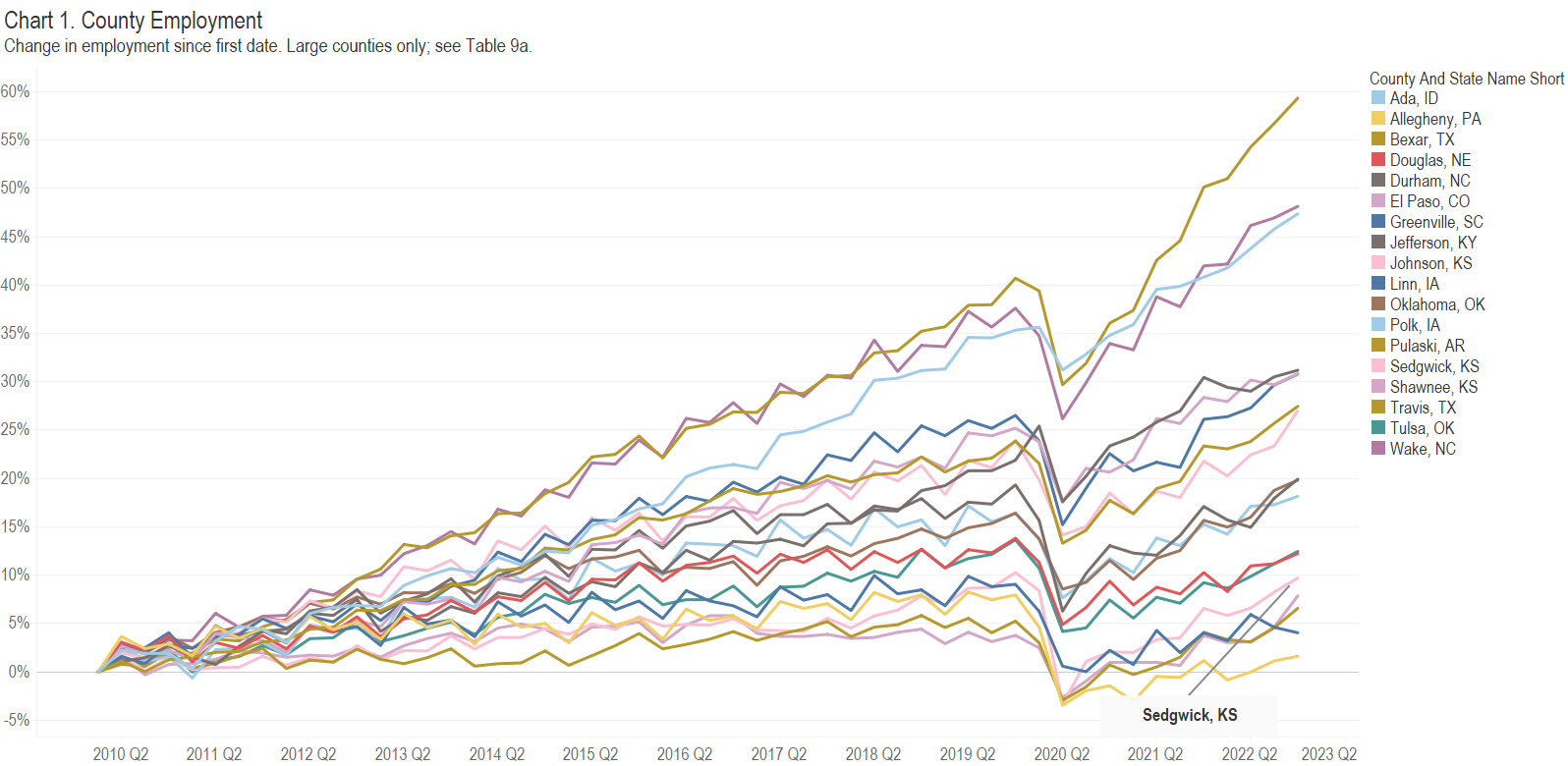

Employment in large counties, including Sedgwick County and others of interest. (more…)

Category: Sedgwick county government

Recent Economic History in Sedgwick County

When deciding whether to vote for incumbent Sedgwick County Commissioners, consider the recent economic history of the county. (more…)

Consider Sedgwick County EMS as You Vote

One of the most important functions of Sedgwick County is providing emergency medical services (EMS). In this, the county has failed. (more…)

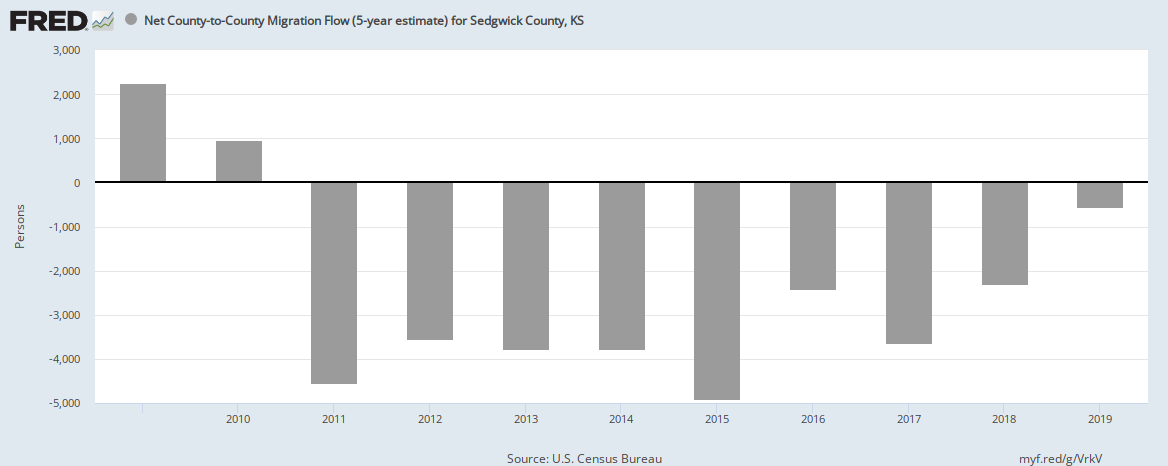

Migration to and from Sedgwick County

Although the rate is slowing, Sedgwick County loses many people to migration. (more…)

Sedgwick County Talent Attraction

In an index ranking counties in talent attraction, Sedgwick County has not performed well, although there is some improvement. (more…)

End this now. Nominate Sarah Lopez.

Sedgwick County Republicans have a chance to do the decent thing and avoid the spectacle of a rump county commissioner.

Rump: a small or inferior remnant or offshoot

especially: a group (such as a parliament) carrying on in the name of the original body after the departure or expulsion of a large number of its members

(from Oxford languages)Now that the vote canvass is complete in Sedgwick County, Sarah Lopez has won the seat for Sedgwick County Commissioner, District 2. The vote count is 17,041 for Lopez and 16,777 for the incumbent Michael O’Donnell, a margin of 264 votes.

O’Donnell is within his rights to ask for (and pay for) a recount, but that is unlikely to change the outcome of the election based on recent experience. In the August 2018 primary election in a different commission district, the loser asked for and paid for a recount. All the ballots were counted by hand, at the precinct level, in a laborious process. In the end, not a single mistake was found.

So Sarah Lopez will become the new commissioner on January 10, 2021. The question is: What to do now? That question needs an answer, because O’Donnell resigned from the office last week. There currently is no commissioner for District 2.

The normal course of events, as prescribed by Kansas law (K.S.A. 25-3902), is that the precinct committeemen and committeewomen in county commission district 2 meet and select a successor to serve the remainder of O’Donnell’s term. Because he was elected as a member of the Republican Party, it is the Republican committeemen/women who make the selection.

It is possible, therefore, that a person will serve as a county commissioner for less than a two-month period, as there are 55 days until January 10. It will take some time to meet and make a selection, as law requires a notice period of seven days or more.

It is unwise to appoint someone to serve in an office for such a short period. It would be a term of perhaps eight weeks at the most, and some of those weeks will be holiday weeks, in which there are no commission meetings. There will be costs to the county. News stories will cover a term of office that will have no meaningful consequence.

But there must be a nominating meeting, and within 14 days, says Kansas law.

The decent and reasonable thing to do is for the nominating convention to meet and select Sarah Lopez to fill the remainder of the term. It is already decided that she will become the commissioner on January 10. It would make sense for her to start her term early, thereby avoiding a lot of time and effort for no good reason. We could avoid a rump.

We should remember that the vacancy in the District 2 commission office arose from the corruption of the immediate past officeholder. He was about to be subject to ouster procedures. He lost his bid for re-election to Sarah Lopez.

We should put this episode behind us, and place Lopez in office now.

Intrust Bank Arena loss for 2019 nears $5 million

A truthful accounting of the finances of Intrust Bank Arena in downtown Wichita shows a large loss.

The true state of the finances of the Intrust Bank Arena in downtown Wichita are not often a subject of public discussion. Arena boosters cite a revenue-sharing arrangement between the county and the arena operator, referring to this as profit or loss. But this arrangement is not an accurate and complete accounting, and it hides the true economics of the arena. What’s missing is depreciation expense.

There are at least two ways of looking at the finance of the arena. Nearly all attention is given to the “profit” (or loss) earned by the arena for the county according to an operating agreement between the county and ASM Global, a company that operates the arena. SMG, the former operator of the arena, merged with another company to form ASM Global.

There are at least two ways of looking at the finance of the arena. Nearly all attention is given to the “profit” (or loss) earned by the arena for the county according to an operating agreement between the county and ASM Global, a company that operates the arena. SMG, the former operator of the arena, merged with another company to form ASM Global.This agreement specifies a revenue sharing mechanism between the county and ASM. For 2109, the accounting method used in this agreement produced a profit, or “net building income,” of $1,021,721 to be split (not equally) between SMG and the county. The county’s share was $310,861. (1)The Operations of INTRUST Bank Arena, as Managed by ASM Global. Independent Auditor’s Report and Special-Purpose Financial Statements. December 31, 2019. Available here.

While described as “profit” by many, this payment does not represent any sort of “profit” or “earnings” in the usual sense. In fact, the introductory letter that accompanies these calculations warns readers that these are “not intended to be a complete presentation of INTRUST Bank Arena’s financial position and results of operations in conformity with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America.” (2)Ibid, page 2.

That bears repeating: This is not a reckoning of profit and loss in any recognized sense. It is simply an agreement between Sedgwick County and SMG as to how SMG is to be paid, and how the county participates.

A much better reckoning of the economics of the Intrust Bank Arena can be found in the 2019 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for Sedgwick County. (3)Sedgwick County. Comprehensive Annual Financial Report of the County of Sedgwick, Kansas for the Year ended December 31, 2019. Available at https://www.sedgwickcounty.org/finance/comprehensive-annual-financial-reports/. This document holds additional information about the finances of the Intrust Bank Arena. The CAFR, as described by the county, “… is a review of what occurred financially last year. In that respect, it is a report card of our ability to manage our financial resources.”

Regarding the arena in 2019, the CAFR states:

The Arena Fund represents the activity of the INTRUST Bank Arena. The facility is operated by a private company; the County incurs expenses only for certain capital improvements or major repairs and depreciation, and receives as revenue only a share of profits earned by the operator, if any, and naming rights fees. The Arena Fund had an operating loss of $5.0 million. The loss can be attributed to $5.0 million in depreciation expense.

Financial statements in the same document show that $4,993,361 was charged for depreciation in 2019. If we subtract the ASM payment to the county of $310,861 from depreciation expense, we learn that the Intrust Bank Arena lost $4,682,500 in 2019.

Depreciation expense is not something that is paid out in cash. That is, Sedgwick County did not write a check for $4,682,500 to pay depreciation expense. Instead, depreciation accounting provides a way to recognize and account for the cost of long-lived assets over their lifespan. It provides a way to recognize opportunity costs, that is, what could be done with our resources if not spent on the arena.

But not many of our civic leaders recognize this, at least publicly. We — frequently — observe our governmental and civic leaders telling us that we must “run government like a business.” The county’s financial report makes mention of this: “Sedgwick County has one business-type activity, the Arena fund. Net position for fiscal year 2019 decreased by $5.0 million to $146.6 million. Of that $146.6 million, $138.9 million is invested in capital assets. The decrease can be attributed to depreciation, which was $5.0 million.” (4)CAFR, page A-10. (emphasis added)

At the same time, these leaders avoid frank and realistic discussion of economic facts. As an example, in years past Commissioner Dave Unruh made remarks that illustrate the severe misunderstanding under which he and almost everyone labor regarding the nature of spending on the arena: “I want to underscore the fact that the citizens of Sedgwick County voted to pay for this facility in advance. And so not having debt service on it is just a huge benefit to our government and to the citizens, so we can go forward without having to having to worry about making those payments and still show positive cash flow. So it’s still a great benefit to our community and I’m still pleased with this report.”

The contention — witting or not — is that the capital investment of $183,625,241 (not including an operating and maintenance reserve) in the arena is merely a historical artifact, something that happened in the past, something that has no bearing today. There is no opportunity cost, according to this view. This attitude, however, disrespects the sacrifices of the people of Sedgwick County and its visitors to raise those funds. Since Kansas is one of the few states that adds sales tax to food, low-income households paid extra sales tax on their groceries to pay for the arena — an arena where they may not be able to afford tickets.

Any honest accounting or reckoning of the performance of Intrust Bank Arena must take depreciation into account. While Unruh is correct that depreciation expense is not a cash expense that affects cash flow, it is an economic reality that can’t be ignored — except by politicians, apparently. The Wichita Eagle and Wichita Business Journal aid in promoting this deception.

The upshot: We’re evaluating government and making decisions based on incomplete and false information, just to gratify the egos of self-serving politicians and bureaucrats.

Reporting on Intrust Bank Arena financial data

In February 2015 the Wichita Eagle reported: “The arena’s net income for 2014 came in at $122,853, all of which will go to SMG, the company that operates the facility under contract with the county, Assistant County Manager Ron Holt said Wednesday.” A reading of the minutes for the February 11 meeting of the Sedgwick County Commission finds Holt mentioning depreciation expense not a single time. Neither did the Eagle article.

In December 2014, in a look at the first five years of the arena, its manager told the Wichita Eagle this: “‘We know from a financial standpoint, the building has been successful. Every year, it’s always been in the black, and there are a lot of buildings that don’t have that, so it’s a great achievement,’ said A.J. Boleski, the arena’s general manager.”

The Wichita Eagle opinion page hasn’t been helpful, with Rhonda Holman opining with thoughts like this: “Though great news for taxpayers, that oversize check for $255,678 presented to Sedgwick County last week reflected Intrust Bank Arena’s past, specifically the county’s share of 2013 profits.” (For some years, the county paid to create a large “check” for publicity purposes.)

That followed her op-ed from a year before, when she wrote: “And, of course, Intrust Bank Arena has the uncommon advantage among public facilities of having already been paid for, via a 30-month, 1 percent sales tax approved by voters in 2004 that actually went away as scheduled.” That thinking, of course, ignores the economic reality of depreciation.

In 2018, the Wichita Eagle reported, based on partial-year results: “Intrust Bank Arena remains profitable but is reporting a 20 percent drop in income this year, despite a bump from the NCAA March Madness basketball tournament. Net income for the first three quarters of this year was about $556,000. That’s down from just shy of $700,000 last year, according to a report to the Sedgwick County Commission.” (5)Lefler, Dion. Despite March Madness, Intrust Bank Arena profit down 20 percent. December 7, 2018. Available at https://www.kansas.com/news/politics-government/article222300675.html. This use of “profitable” is based only on the special revenue-sharing agreement, not generally accepted accounting principles.

Even our city’s business press — which ought to know better — writes headlines like Intrust Bank Arena tops $1.1M in net income for 2015 without mentioning depreciation expense or explaining the non-conforming accounting methods used to derive this number.

All of these examples are deficient in an important way: They contribute confusion to the search for truthful accounting of the arena’s finances. Recognizing depreciation expense is vital to understanding profit or loss, we’re not doing that.

References

References ↑1 The Operations of INTRUST Bank Arena, as Managed by ASM Global. Independent Auditor’s Report and Special-Purpose Financial Statements. December 31, 2019. Available here. ↑2 Ibid, page 2. ↑3 Sedgwick County. Comprehensive Annual Financial Report of the County of Sedgwick, Kansas for the Year ended December 31, 2019. Available at https://www.sedgwickcounty.org/finance/comprehensive-annual-financial-reports/. ↑4 CAFR, page A-10. ↑5 Lefler, Dion. Despite March Madness, Intrust Bank Arena profit down 20 percent. December 7, 2018. Available at https://www.kansas.com/news/politics-government/article222300675.html.

Intrust Bank Arena economic impact holds mistake

A report on the economic impact of the first ten years of operation of the Intrust Bank Arena in downtown Wichita incorrectly reported tax revenue.

Recently Intrust Bank Arena in downtown Wichita promoted the results of an analysis of the economic impact of the arena through its first ten years of operation. 1 The arena partnered with the Center for Economic Development and Business Research at Wichita State University to conduct the study. 2

In all, the report claims $2.7 million over ten years in Sedgwick County guest tax revenue paid by out-of-town arena visitors who stayed in local hotels. But while the county has a guest tax, it does not raise nearly the dollars shown in the report.

The transient guest tax, sometimes called a guest tax or bed tax, is a tax on a hotel bill. It is collected in addition to retail sales tax. In the City of Wichita, hotel guests pay 7.5 percent retail sales tax, an additional six percent guest tax, and an additional 2.75 percent city tourism fee. If the hotel is located within a Community Improvement District, an additional tax of up to two percent is collected.

The guest tax for Sedgwick County was last revised in 2006. 3 The rate is five percent. The ordinance says that the tax “… shall be levied in the unincorporated area of Sedgwick County, Kansas …”

The term unincorporated area is key, meaning the portions of the county that are not within an incorporated town or city. Reports from the Kansas Department of Revenue show there is just one establishment in Sedgwick County that files a guest tax report. 4 For comparison, 108 establishments in the City of Wichita file guest tax reports. These are located in the city limits and are not in the unincorporated area of the county, and therefore not subject to the county guest tax.

How much does Sedgwick County collect in guest tax? The reports from the Kansas Department of Revenue don’t say. The value is suppressed to protect confidentiality, given that there is just one filing establishment in the unincorporated area of the county.

We do know, according to the economic impact report, that the one hotel in unincorporated Sedgwick County collects $351,656 per year in guest tax (annualized over the period 2015 to 2019.) Since the guest tax rate is five percent, that implies $7 million in annual sales, which would be collected by a hotel selling 191 rooms per day at a rate of $100 per day, 365 days per year.

Is there such a hotel in unincorporated Sedgwick County? It’s unlikely. Consider this one hotel with $351,656 in guest tax collections by arena visitors compared to the $421,987 reported for all hotels in the City of Wichita, again for arena visitors. (The Wichita guest tax rate is slightly higher at six percent, so the comparison is not strictly equal.)

Remember: According to the analysis, this level of activity is generated just by visitors attending events at Intrust Bank Arena.

I think it’s safe to say there is a mistake. Correspondence with CEDBR, the organization that prepared the analysis, confirms that county guest tax was incorrectly estimated, and a new version reports $0 in county guest tax. 5 CEDBR says no numbers were changed other than the county guest tax and totals that included it.

While it is unfortunate that CEDBR made this mistake, the use of the analysis by downstream consumers teaches us something about economic development, the data supporting it, and its practitioners.

As an example, the management of Intrust Bank Arena issued a press release touting the analysis and its findings. Regarding tax collections, the announcement reports, “The fiscal impact of visitors to the area for INTRUST Bank Arena events that occurred in 2010-2019 was approximately $12 million in tax revenue generated.”

What’s interesting is that the release cites only the retail sales tax revenue. It omits the guest tax revenue, which is — according to the analysis that was available at the time of the press release — about $6 million. That’s half as much as the retail sales tax, but it was not included in a press release touting economic impact.

An excerpt from the first page of the CEDBR analysis. Click for larger.

An excerpt from the first page of the CEDBR analysis. Click for larger.Why didn’t the arena use the guest tax collections, thereby reporting $18 million in tax revenue collected from visitors rather than $12 million? It wasn’t due to concern over the accuracy of the guest tax collections, as arena management told me they were not aware of CEDBR’s error. But because the press release did not mention the erroneous guest tax, arena management says there is no need to correct the press release. This is correct, and it reveals the mistake in not including guest tax revenue.

Adding to our learning about the use of data in economic development is this: Of the sales tax collected by hotels in Wichita, about 87 percent belongs to the State of Kansas, with the remainder shared by Wichita and Sedgwick County. For guest tax, however, all is returned to the city, except for a small administrative fee of two percent. So of the $12 million in retail sales tax revenue promoted by arena management, about $1.5 million was shared by the city and county. 6 For the purported $6 million in guest tax revenue, all went to the city and county, except for the administrative fee.

We also learn about the diligence of Sedgwick County Commissioner Pete Meitzner (district 1) in examining this data. He is quoted in the arena’s press release. But it’s quite easy to see that the analysis erroneously reports county guest tax revenue.

Besides this mistake, there are other areas of concern regarding this analysis of the economic impact of the arena. One is that this report mentions revenue but not costs. 7

The second is that before Intrust Bank Arena opened in downtown, the county owned another arena. That former arena generated economic activity and economic impact, too, including NCAA men’s basketball tournament games. A thorough analysis should look at the marginal activity created by the new arena.

—

Notes- INTRUST Bank Arena Reports Economic Impact Study Results Through First 10 Years. February 14, 2020. Available at https://www.intrustbankarena.com/release/366/intrust-bank-arena-reports-economic-impact-study-results-through-first-10-years/. ↩

- Analysis by CEDBR, version 2, dated 1/6/2020. The document does not seem to be available online at either the arena website or Sedgwick County, but it has been preserved. Available at https://drive.google.com/file/d/11LZfbEXxYPfjLs02zE2fdUaWrQYJiUzm/view. ↩

- Sedgwick County. A charter resolution exempting Sedgwick County, Kansas, from the provisions of k.S.A. 12-1692, 12-1693, 12-1694, 12-1694a, 12-1695, and providing substitute and additional provisions on the same subject relating to the levy of a transient guest tax in the unincorporated area of Sedgwick County and providing for purposes of expenditure of such funds; and repealing charter resolution #32. Available at https://library.municode.com/ks/sedgwick_county/codes/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=SECOKACO_APXACHRE_NO._59. ↩

- Kansas Department of Revenue. Transient Guest Tax Rate and Filer Report. Available at https://www.ksrevenue.org/pdf/tgratesfilers.pdf. ↩

- Analysis by CEDBR, version 3, dated 2/26/2020. Available at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1uhLJBr5PXJ_Y6RaiP13bHNRAK08fEVg4/view. ↩

- Specifically, the analysis reports $983,449 in sales tax to the city and $703,714 to the county, for a total of $1,687,163. ↩

- It’s common for officials to talk as though there is no cost or expense in owning the arena, because a sales tax was used to pre-fund the arena. After the funds were in place, the arena was built. But, see Weeks, Bob. The finances of Intrust Bank Arena in Wichita. Available at https://wichitaliberty.org/sedgwick-county-government/the-finances-of-intrust-bank-arena-in-wichita/. For annual expenses, in a presentation to Sedgwick County Commissioners in February, county staff reported $1,991,471.99 in expenses charged to the arena’s reserve fund. This was offset by $722,933.65 in revenue, mostly from a revenue-sharing agreement with the arena’s operator and from the sale of naming rights. The declining balance in the arena’s reserve fund led Commissioner David Dennis to wonder if a special tax district could be established to provide more revenue to cover these expenses. See https://drive.google.com/file/d/1UbAfjQaIWQOzrYzIWqKdBIbrqFMDlfX-/view ↩

There are at least two ways of looking at the finance of the arena. Nearly all attention is given to the “profit” (or loss) earned by the arena for the county according to an operating agreement between the county and

There are at least two ways of looking at the finance of the arena. Nearly all attention is given to the “profit” (or loss) earned by the arena for the county according to an operating agreement between the county and