Tag: Wichita Eagle opinion watch

-

For Wichita Eagle, no concern about relationships

Should the Wichita Eagle, a city’s only daily newspaper and the state’s largest, be concerned about the parties to its business relationships?

-

Wrong direction for Wichita public schools

A letter in the Wichita Eagle illustrates harmful attitudes and beliefs of the public school establishment.

-

The Wichita Eagle on Kansas sales tax exemptions

The Wichita Eagle editorial board writes an editorial that gives false hope to advocates of more taxation and more spending.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Wichita and Kansas economics, and government investment

Wichita sells a hotel, more subsidy for downtown, Kansas newspaper editorialists fall for a lobbyist’s tale, how Kansas can learn from Arizona schools, and government investment.

-

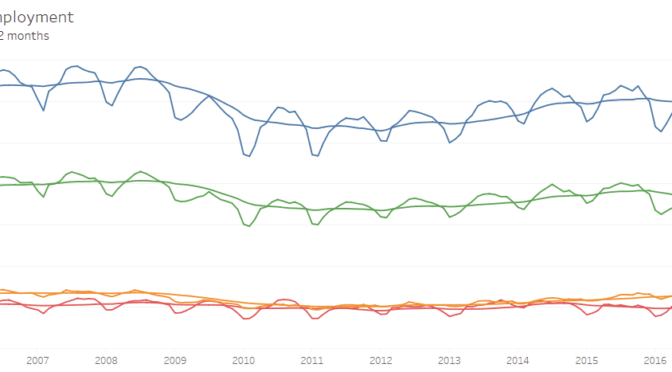

Kansas construction employment

Tip to the Wichita Eagle editorial board: When a lobbying group feeds you statistics, try to learn what they really mean.

-

Intrust Bank Arena loss for 2015 is $4.1 million

The depreciation expense of Intrust Bank Arena in downtown Wichita recognizes and accounts for the sacrifices of the people of Sedgwick County and its visitors to pay for the arena.

-

Wichita Eagle opinion watch

Another nonsensical editorial from the Wichita Eagle.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: News media, hollow Kansas government, ideology vs. pragmatism

In this episode of WichitaLiberty.TV: New outlets for news, and criticism of the existing. Is Kansas government “hollowed out?” Ideology and pragmatism.

-

Wichita mayor’s counterfactual op-ed

Wichita’s mayor pens an op-ed that is counter to facts that he knows, or should know.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Trump and the Wichita Eagle, property rights and blight, teachers union, and capitalism

Was it “Trump” or “Bernie” that incited a fight, and how does the Wichita Eagle opine? Economic development in Wichita. Blight and property rights. Teachers unions. Explaining capitalism.

-

‘Trump, Trump, Trump’ … oops!

An event in Wichita that made national headlines has so far turned out to be not the story news media enthusiastically promoted.

-

What else can Wichita do for downtown companies?

With all Wichita has done, it may not be enough.