Tag: Downtown Wichita arena

-

Intrust Bank Arena loss for 2019 nears $5 million

A truthful accounting of the finances of Intrust Bank Arena in downtown Wichita shows a large loss.

-

The finances of Intrust Bank Arena in Wichita

A truthful accounting of the finances of Intrust Bank Arena in downtown Wichita shows a large loss. Despite hosting the NCAA basketball tournament, the arena’s “net income” fell.

-

Wichita considers a new stadium

The City of Wichita plans subsidized development of a sports facility as an economic driver. Originally published in July 2017.

-

Intrust Bank Arena loss for 2017 is $4,222,182

As in years past, a truthful accounting of the finances of Intrust Bank Arena in downtown Wichita shows a large loss.

-

Naftzger Park contract: Who is in control?

The City of Wichita says it retains final approval on the redesign of Naftzger Park, but a contract says otherwise.

-

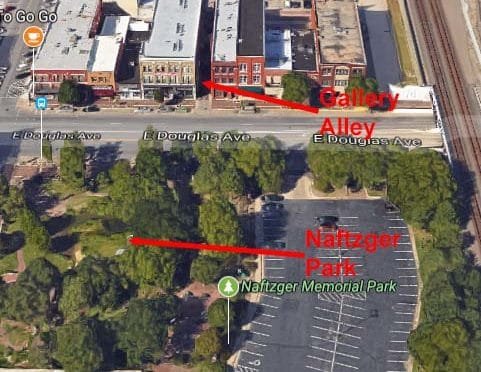

Downtown Wichita gathering spaces that don’t destroy a park

Wichita doesn’t need to ruin a park for economic development, as there are other areas that would work and need development.

-

Naftzger Park concerts and parties?

In Wichita, a space for outdoor concerts may be created across the street from where amplified concerts are banned.

-

In Wichita, new stadium to be considered

The City of Wichita plans subsidized development of a sports facility as an economic driver.

-

Intrust Bank Arena loss for 2016 is $4,293,901

As in years past, a truthful accounting of the finances of Intrust Bank Arena in downtown Wichita shows a large loss.

-

Naftzger Park in Downtown Wichita

An information resource regarding the future of Naftzger Park in downtown Wichita.

-

On Wichita’s STAR bond promise, we’ve heard it before

Are the City of Wichita’s projections regarding subsidized development as an economic driver believable?

-

Intrust Bank Arena loss for 2015 is $4.1 million

The depreciation expense of Intrust Bank Arena in downtown Wichita recognizes and accounts for the sacrifices of the people of Sedgwick County and its visitors to pay for the arena.