Background on tax increment financing (TIF) as applied to Naftzger Park in downtown Wichita.

The City of Wichita has proposed using tax increment financing (TIF) revenue to redevelop Naftzger Park in downtown Wichita. Various city officials have said something along these lines: There is a pot of money — 1.5 million dollars — available for use on Naftzger Park, and this money can’t be used for any other purpose. Also, it’s implied that if this money is not used on Naftzger Park, this money will not be available for any purpose, almost as though the money will be wasted.

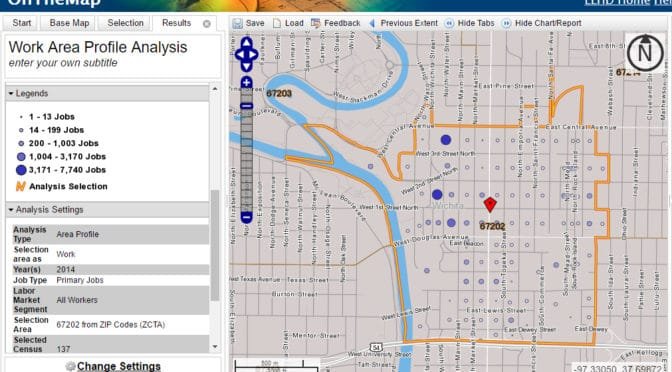

The source of the money is tax increment financing (TIF). This is a method of public finance whereby future property tax revenues are redirected from their normal flow to something else. The amount of taxes that are paid at the time of the formation of the TIF district is called the base, which is a function of the district’s original assessed value. The plan is that as new property is built or existing property renovated in the TIF district, there is more assessed value, and more taxes are levied and collected. The amount of taxes paid each year above the base is called the increment. It is these incremental taxes that are captured and rerouted. Because TIF is usually applied to blighted areas and the property is not highly valued, the base is usually low. In successful TIF projects, the increment can be very large. 1

To where are the incremental taxes redirected? Generally, to the benefit of property owners in the TIF district. 2 While there are restrictions on how TIF dollars may be spent, I don’t think any developers within TIF districts have not been able to take full advantage of the TIF dollars that are available, although Naftgzer Park is a special case (see below).

Advocates of TIF make it sound as though it is free money. They often say that if the proposed project does not receive TIF financing, it can’t be built. This is the “but for” justification: But for the benefit of TIF, nothing will happen. Without TIF there will be no development, and no future incremental taxes will be collected.

There are several issues with this line of thinking. First, the but for rationale is subject to abuse. Developers who want to use TIF have a large monetary incentive to make it appear as though their projects are not financially viable without TIF. That’s the meaning of but for. To make their case for TIF, developers supply financial projections to cities, and the city usually accepts them at face value. These financial projections rely on many assumptions about the future, often 20 or more years in the future. For example, what will be the occupancy rate and average room rate for a proposed hotel in 15 years? Forecasting these values for next year is difficult enough. Yet, it is projections like these that form the basis of the necessity of TIF.

City officials do not have the expertise to evaluate these financial projections. If citizens want to see these projections, the City of Wichita will not supply them, in most cases.

Second: The pleas for TIF made by developers are sometimes plainly false. In Wichita, a developer wanted to build a grocery store using TIF and other incentives. He told the city he has “researched every possible way” to make the project work, and it would not work without TIF. 3 A representative of the developer told the city council, “There will not be a building on that corner if this [TIF] is not passed today. … That new building would not be built. I absolutely can tell you that because we have spent months … trying to figure out a way to finance a project in that area.”

The city’s chief economic development official told the council, “We know, for example, from the developer’s perspective in terms of how much they will make in lease payments from the Save-A-Lot operator, how much that is, and how much debt that will support, and how much funds the developer can raise personally for this project. That has, in fact, left a gap, and these numbers that you’ve seen today reflect what that gap is.” 4

While the city approved TIF, the county did not. So TIF was not available, and the developer abandoned the project. But: A different developer built the same grocery store and additional retail space at the same location without TIF. It is still in operation six years later.

Third: If it is true that we can’t have new development without TIF, there may be obstacles in place that should be removed so that development can take place without TIF.

Not free money

TIF has a cost. A real cost. If we don’t recognize that, then we must reconsider the foundation of local tax policy.

In Wichita, as in most cities, the largest consumers of property tax dollars are the city, county, and school district. All justify their tax collections by citing the services they provide: Law enforcement, fire protection, education, etc. It is for providing these services that we pay local taxes.

Within a TIF district, however, the new property tax dollars — the increment — do not go to the city, county, and school district to pay for services. Instead, these dollars are used in ways that benefit the development: Property acquisition, site preparation, utilities, drainage, street improvements, streetscape amenities, public outdoor spaces, landscaping, and parking facilities, according to the city’s explanation.

Yet, the new development will undoubtedly demand and consume the services local government provides — law enforcement, fire protection, and education. But its incremental property taxes do not pay for these, as they have been diverted elsewhere. (The base property taxes still go to pay for these services, but the base is usually low.) Instead, others must pay the cost of providing services to the TIF development, or accept reduced levels of service as existing service providers are saddled with new demand.

Supporters of TIF argue that developers aren’t getting a free ride. The city isn’t giving them cash, they say. The owners of the TIF development will be paying their full share of higher property taxes in the future. That’s true. But, these new tax dollars are spent for their benefit, not to pay for the cost of government.

We’re left with an uncomfortable situation. City officials tell us that we must pay property taxes so the city can provide services. (In fact, right now the Wichita city manager is recommending increasing property taxes to pay for more police officers.)

At the same time, however, the city creates special classes of people who use services but don’t pay for them.

Yes, the city and developers cite the but for argument, arguing that without the benefit of TIF, there won’t be new development and new demand for services. But we’ve seen that the but for rationale is dubious and subject to abuse.

Of note: At a recent public meeting regarding Naftzger Park, someone asked if some of the $1.5 million could be used for more police officers. The answer from city officials was “no.” That answer is correct. But in the normal case, part of this $1.5 million would be available to pay for more police.

Also: The redevelopment district in which incremental taxes will be redirected to Naftzger Park includes a number of properties that are already developed.

Allowed uses: It’s just infrastructure

In their justification of TIF, proponents may say that TIF dollars are spent only on allowable purposes. Usually a prominent portion of TIF dollars are spent on things that are related to infrastructure, as listed above. This allows TIF proponents to say the money isn’t really being spent for the benefit of a specific project. It’s spent on infrastructure, they say, which they contend is something that benefits everyone, not one project specifically. Therefore, everyone ought to pay.

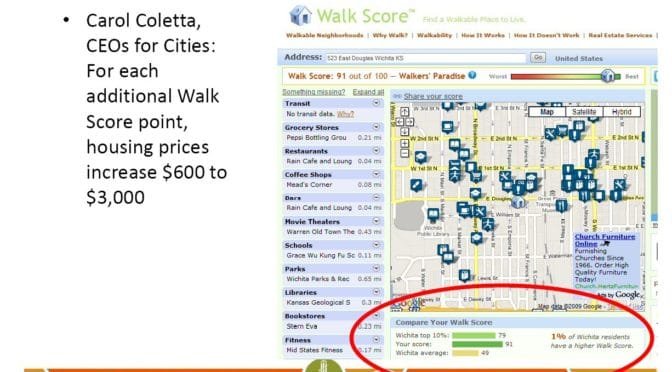

But this isn’t the case. Often non-TIF developers pay for significant infrastructure at their own expense. An example is the Waterfront development in northeast Wichita. There is a street that winds through the development, Waterfront Parkway. To anyone driving or walking in this area, they would think this is just another city street — although a very nicely designed and landscaped street. But the city did not pay for this street. Private developers paid $1,672,000 for this infrastructure, and then deeded it to the city. The same developers paid for street lights, traffic signals, sewers, water pipes, and turning lanes on major city streets. In order to build the Waterfront development, private developers paid for infrastructure, with a total cost of these projects at one time being $3,334,500. It has likely risen since then. 5

In the case of Naftzger Park, it’s argued that the park benefits everyone. Therefore, it’s akin to infrastructure. In reality, the park is more like the front yard of a proposed hotel and a nearby building, being developed for their owner’s benefit. The developers of these are managing, along with the city, the plans for Naftzger Park. Incredibly, applications to be the park’s architect were sent not to the city, but to the private developers. 6

Further: Park improvements were not an allowed use of TIF funds when the Center City South TIF was formed in 2007. So the city amended the TIF district plan to allow for TIF funds to be used to redevelop Naftzger Park. 7

Redirect your taxes, not mine

The Wichita Downtown Development Corporation (WDDC) is funded, primarily, by property taxes. A district known as the Self-Supported Municipal Improvement District (SSMID) levies a property tax in a district roughly defined as from Kellogg north to Central, and the Arkansas River east to Washington Street. In 2011 the mill levy was 5.950 and raised nearly $600,000 in revenue. 8 For 2016 the mill levy was 7.140. With an assessed value of $92,901,423, the SSMID tax ought to raise about $663,000. 9

All the property tax money raised by the SSMID is used to fund WDDC.

Now, WDDC — one of the leading advocates for the use of TIF in downtown Wichita — is quite happy to see incremental tax dollars redirected away from the city, county, and school district to benefit TIF developers. You might think that WDDC would also participate in this — purportedly — beneficial arrangement, consenting for its share of property tax to also be redirected for the benefit of developers.

Guess again. The SSMID — nearly the only source of funding for WDDC — is exempted from having its tax revenue capture by TIF and redirected to another purpose.

—

Notes

- Weeks, Bob. Wichita TIF projects: some background. Available at https://wichitaliberty.org/wichita-government/wichita-tif-projects-background/. ↩

- The Center City South TIF district is an unusual case in that only 70 percent of the incremental taxes are redirected. ↩

- Weeks, Bob. In Wichita Planeview neighborhood: Yes, we have! Available at https://wichitaliberty.org/wichita-government/in-wichita-planeview-neighborhood-yes-we-have/. ↩

- Weeks, Bob. For Wichita, Save-A-Lot teaches a lesson. Available at https://wichitaliberty.org/wichita-government/for-wichita-save-a-lot-teaches-a-lesson/. ↩

- Weeks, Bob. Wichita TIF projects: some background. Available at https://wichitaliberty.org/wichita-government/wichita-tif-projects-background/. ↩

- City of Wichita. Request for Qualification No. – FP740043. Available at https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B97azj3TSm9MQ1ZVcXVsNVQ2dkE/view?usp=sharing. ↩

- Wichita city council agenda packet for May 16, 2016, agenda item IV-1. ↩

- Wichita city ordinance 48-786. Available at http://wichitaks.granicus.com/MetaViewer.php?view_id=2&clip_id=820&meta_id=65004. ↩

- Sedgwick County Clerk’s Office and author’s calculations. ↩