Tag: Wichita Convention and Visitors Bureau

-

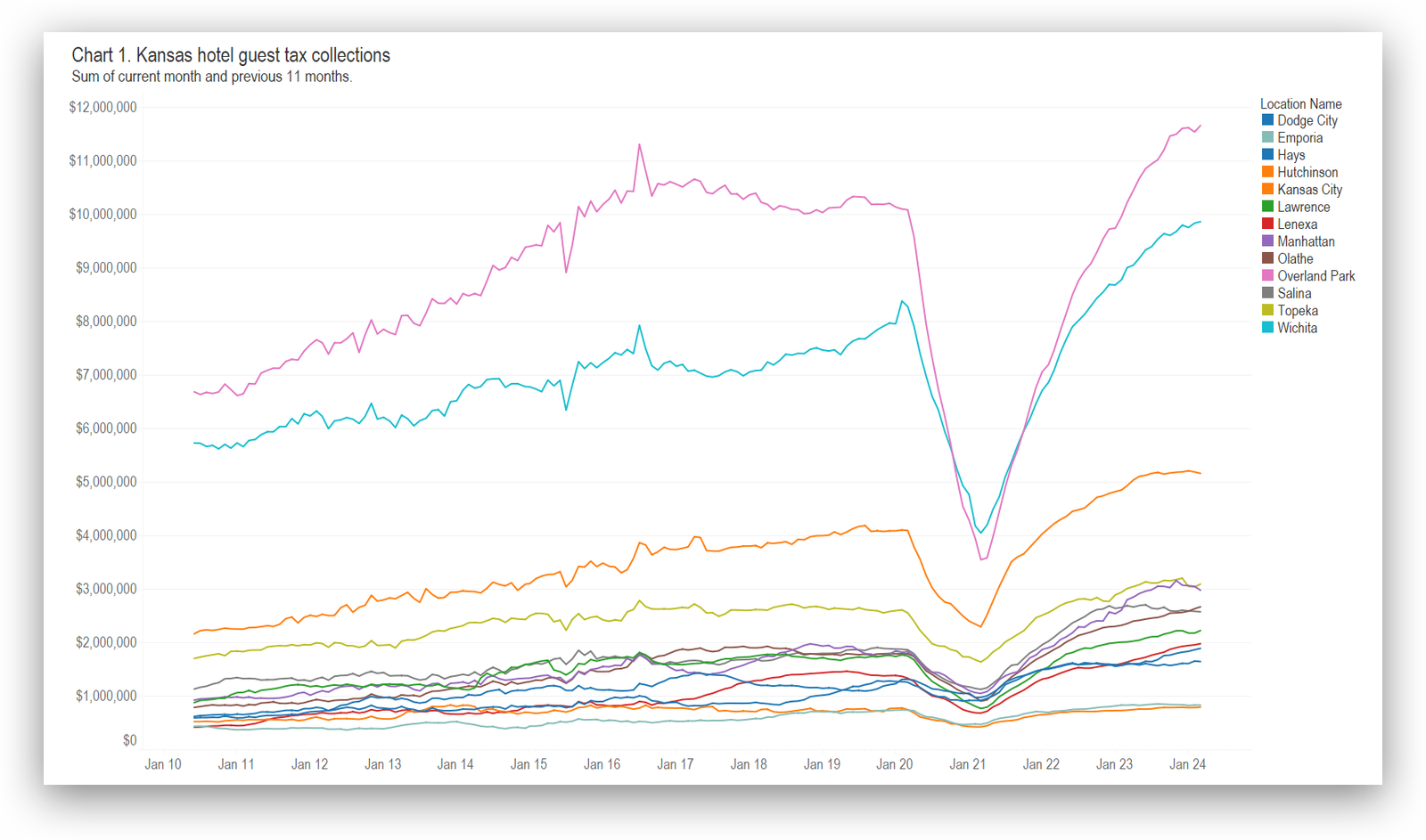

Updated: Kansas hotel guest tax collections

Kansas hotel guest tax collections presented in an interactive visualization. Updated with data through March 2024.

-

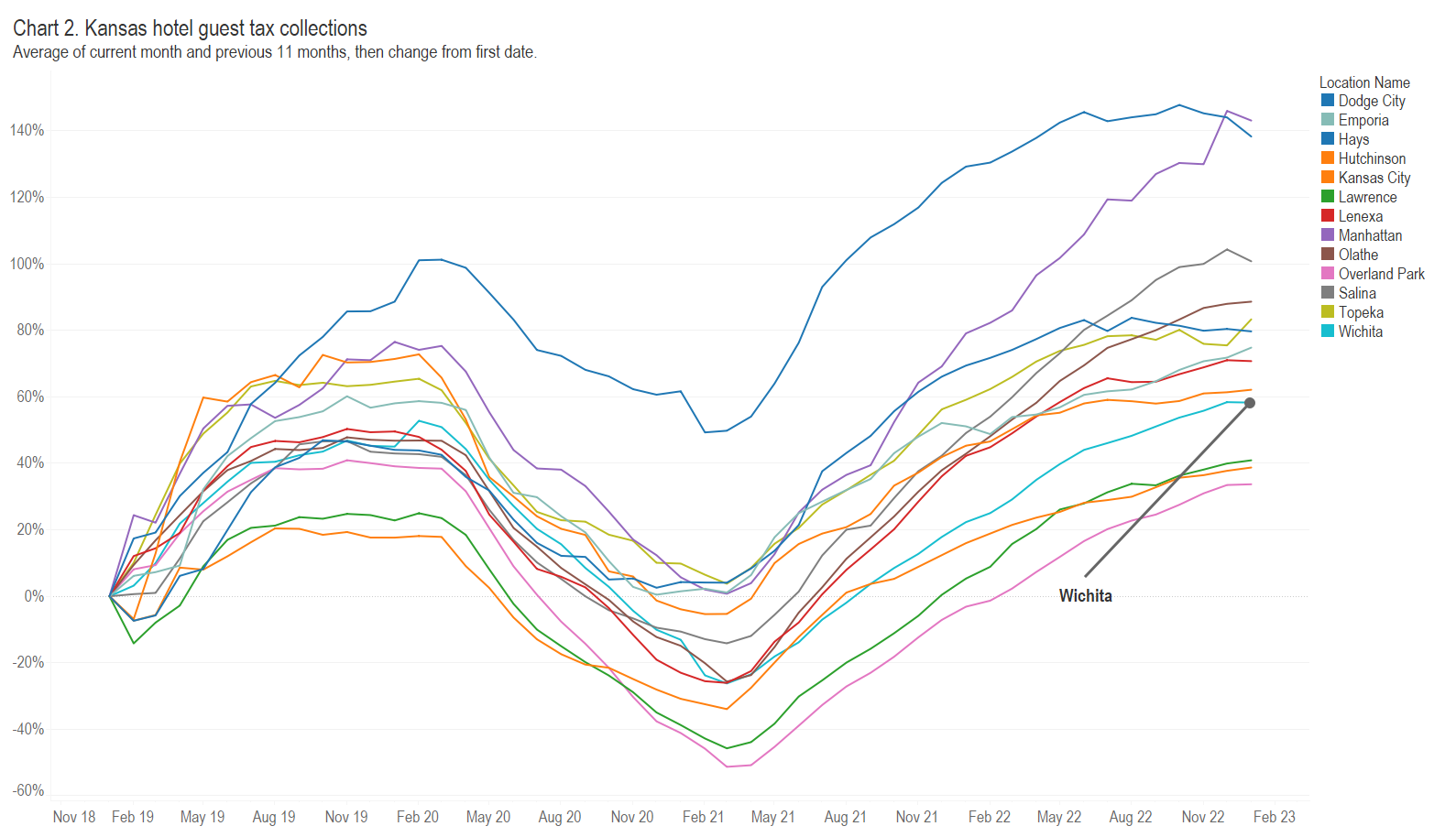

Updated: Kansas hotel guest tax collections

Kansas hotel guest tax collections presented in an interactive visualization. Updated with data through January 2023.

-

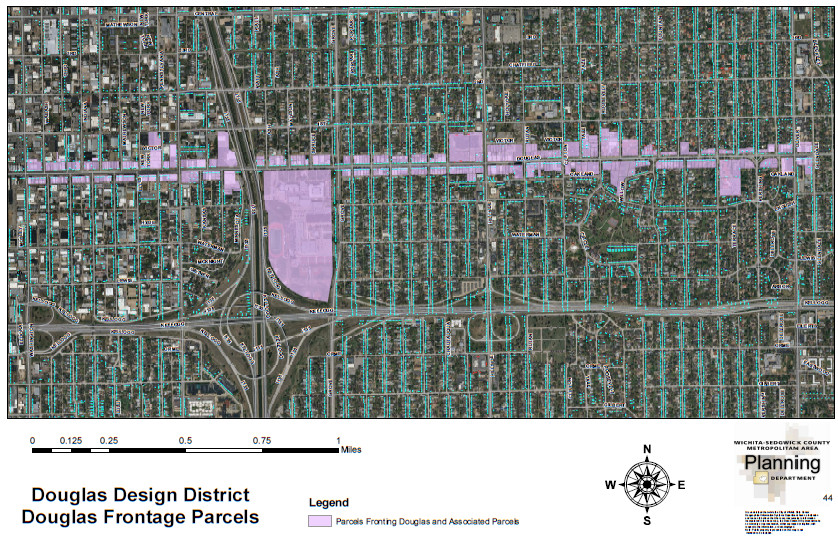

Business improvement district on tap in Wichita

The Douglas Design District seeks to transform from a voluntary business organization to a tax-funded branch of government.

-

More Wichita planning on tap

We should be wary of government planning in general. But when those who have been managing and planning the foundering Wichita-area economy want to step up their management of resources, we risk compounding our problems.

-

In Wichita, respecting the people’s right to know

The City of Wichita says it values open and transparent government. But the city’s record in providing information and records to citizens is poor, and there hasn’t been much improvement.

-

Business improvement district proposed in Wichita

The Douglas Design District proposes to transform from a voluntary business organization to a tax-funded branch of government (but doesn’t say so).

-

Wichita tourism fee budget

The Wichita City Council will consider a budget for the city’s tourism fee paid by hotel guests.

-

Liquor tax and the NCAA basketball tournament in Wichita

Liquor enforcement tax collections provide insight into the economic impact of hosting NCAA basketball tournament games in Wichita.

-

Effect of NCAA basketball tournament on Wichita hotel tax revenues

Hotel tax collections provide an indication of the economic impact of hosting a major basketball tournament.

-

Briefs

Reminds me of the Wichita flag Wichita Eagle Opinion Line, December 5, 2017: “So Wichita wants to put its flag on license plates. I hope not. Every time I see it, it reminds me of how much it looks like the KKK emblem.” I’ve noticed this too. Have you? Here is the center of the…

-

During Sunshine Week, here are a few things Wichita could do

The City of Wichita says it values open and transparent government, but the city lags far behind in providing information and records to citizens.

-

In Wichita, we’ll not know how this tax money is spent

Despite claims to the contrary, the attitude of the City of Wichita towards citizens’ right to know is poor, and its attitude will likely be reaffirmed this week.