Tag: Wichita Chamber of Commerce

-

Wichita Metro Chamber of Commerce on the campaign trail

We want to believe that The Wichita Metro Chamber of Commerce and its PAC are a force for good. Why does the PAC need to be deceptive and untruthful?

-

A look at a David Dennis campaign finance report

It’s interesting to look at campaign finance reports. Following, a few highlights on a report from David Dennis, a candidate for Sedgwick County Commission.

-

Wichita officials, newspaper, just don’t get it on Ex-Im Bank

Wichita’s establishment prefers cronyism over capitalism.

-

Wichita Chamber calls for more cronyism

By advocating for revival of the Export-Import Bank of the United States, the Wichita Metro Chamber of Commerce continues its advocacy for more business welfare, more taxes, more wasteful government spending, and more cronyism

-

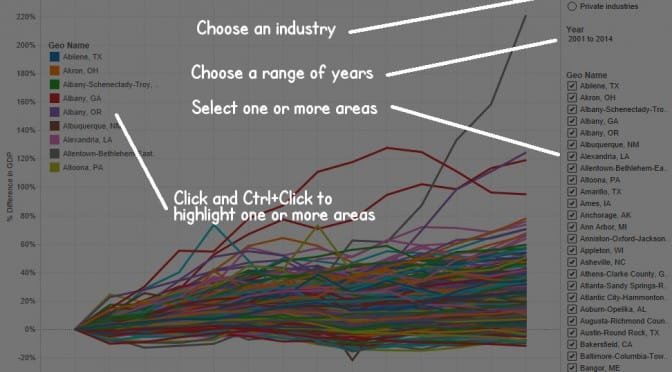

Wichita’s growth in gross domestic product

An interactive visualization of gross domestic product for metropolitan areas.

-

Wichita Chamber speaks on county spending and taxes

The Wichita Metro Chamber of Commerce urges spending over fiscally sound policies and tax restraint in Sedgwick County.

-

A Wichita Shocker, redux

Based on events in Wichita, the Wall Street Journal wrote “What Americans seem to want most from government these days is equal treatment. They increasingly realize that powerful government nearly always helps the powerful …” But Wichita’s elites don’t seem to understand this.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: That piano, the effect of school choice on school districts, and making Wichita inviting.

The purchase of a piano by a Kansas school district is a teachable moment. Then, how do school choice programs affect budgets and performance of school districts? Finally, making Wichita an inclusive and attractive community.

-

Making Wichita an inclusive and attractive community

There are things both easy and difficult Wichita could do to make the city inclusive and welcoming of all, especially the young and diverse.

-

Year in Review: 2014

Here is a sampling of stories from Voice for Liberty in 2014.

-

Economic development in Sedgwick County

The issue of awarding an economic development incentive reveals much as to why the Wichita-area economy has not grown.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: A downtown parking garage deal, academic freedom attacked at KU, and classical liberalism

In this episode of WichitaLiberty.TV: While chair of the Wichita Metro Chamber of Commerce, a Wichita business leader strikes a deal that’s costly for taxpayers. A Kansas University faculty member is under attack from groups that don’t like his politics. Then, how can classical liberalism help us all get along with each other?