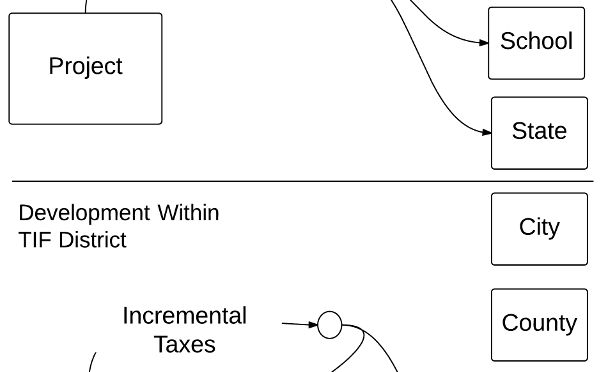

Tax increment financing disrupts the usual flow of tax dollars, routing funds away from cash-strapped cities, counties, and schools back to the TIF-financed development. TIF creates distortions in the way cities develop, and researchers find that the use of TIF means lower economic growth.

The consideration this week by the Wichita City Council of two project plans in tax increment financing districts offers an opportunity to examine the issues surrounding TIF.

How TIF works

A TIF district is a geographically-defined area.

In Kansas, TIF takes two or more steps. The first step is that cities or counties establish the boundaries of the TIF district. After the TIF district is defined, cities then must approve one or more project plans that authorize the spending of TIF funds in specific ways. (The project plan is also called a redevelopment plan.) In Kansas, overlapping counties and school districts have an opportunity to veto the formation of the TIF district, but this rarely happens. Once the district is formed, cities and counties have no ability to object to TIF project plans.

(Cities, counties, and school districts still receive the base tax payments, but these are usually small, much smaller than the incremental taxes. In non-TIF development, these agencies still receive the base taxes too, plus whatever taxes result from improvement of the property — the “increment,” so to speak. Or simply, all taxes.)

The Kansas law governing TIF, or redevelopment districts as they are also called, starts at K.S.A. 12-1770.

TIF and public policy

Originally most states included a “but for” test that TIF districts must meet. That is, the proposed development could not happen but for the benefits of TIF. Many states have dropped this requirement. At any rate, developers can always present proposals that show financial necessity for subsidy, and gullible government officials will believe.

Similarly, TIF was originally promoted as a way to cure blight. But cities are so creative and expansive in their interpretation of blight that this requirement, if it still exists, has little meaning.

The rerouting of property taxes under TIF goes against the grain of the way taxes are usually rationalized. We use taxation as a way to pay for services that everyone benefits from, and from which we can’t exclude people. An example would be police protection. Everyone benefits from being safe, and we can’t exclude people from benefiting from police protection.

So when we pay property tax — or any tax, for that matter — people may be comforted knowing that it goes towards police and fire protection, street lights, schools, and the like. (Of course, some is wasted, and government is not the only way these services, especially education, could be provided.)

But TIF is contrary to this justification of taxes. TIF allows property taxes to be used for one person’s (or group of persons) exclusive benefit. This violates the principle of broad-based taxation to pay for an array of services for everyone. Remember: What was the purpose of the TIF bonds? To pay for things that benefited the development. Now, the development’s property taxes are being used to repay those bonds instead of funding government.

One more thing: Defenders of TIF will say that the developers will pay all their property taxes. This is true, but only on a superficial level. We now see that the lion’s share of the property taxes paid by TIF developers are routed back to them for their own benefit.

It’s only infrastructure

In their justification of TIF in general, or specific projects, proponents may say that TIF dollars are spent only on allowable purposes. Usually a prominent portion of TIF dollars are spent on infrastructure. This allows TIF proponents to say the money isn’t really being spent for the benefit of a specific project. It’s spent on infrastructure, they say, which they contend is something that benefits everyone, not one project specifically. Therefore, everyone ought to pay.

This attitude is represented by a comment left at Voice for Liberty, which contended: “The thing is that real estate developers do not invest in public streets, sidewalks and lamp posts, because there would be no incentive to do so. Why spend millions of dollars redoing or constructing public streets when you can not get a return on investment for that”

This perception is common: that when we see developers building something, the City of Wichita builds the supporting infrastructure at no cost to the developers. But it isn’t quite so. About a decade ago a project was being developed on the east side of Wichita, the Waterfront. This project was built on vacant land. Here’s what I found when I searched for City of Wichita resolutions concerning this project:

In a TIF district, these things are called “infrastructure” and will be paid for by the development’s own property taxes — taxes that must be paid in any case. Outside of TIF districts, developers pay for these things themselves.

If not for TIF, nothing will happen here

Generally, TIF is justified using the “but-for” argument. That is, nothing will happen within a district unless the subsidy of TIF is used. Paul F. Byrne explains:

“The but-for provision refers to the statutory requirement that an incentive cannot be awarded unless the supported economic activity would not occur but for the incentive being offered. This provision has economic importance because if a firm would locate in a particular jurisdiction with or without receiving the economic incentive, then the economic impact of offering the incentive is non-existent. … The but-for provision represents the legislature’s attempt at preventing a local jurisdiction from awarding more than the minimum incentive necessary to induce a firm to locate within the jurisdiction. However, while a firm receiving the incentive is well aware of the minimum incentive necessary, the municipality is not.”

It’s often thought that when a but-for justification is required in order to receive an economic development incentive, financial figures can be produced that show such need. Now, recent research shows that the but-for justification is problematic. In Does Chicago’s Tax Increment Financing (TIF) Programme Pass the ‘But-for’ Test? Job Creation and Economic Development Impacts Using Time-series Data, author T. William Lester looked at block-level data regarding employment growth and private real estate development. The abstract of the paper describes:

“This paper conducts a comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness of Chicago’s TIF program in creating economic opportunities and catalyzing real estate investments at the neighborhood scale. This paper uses a unique panel dataset at the block group level to analyze the impact of TIF designation and investments on employment change, business creation, and building permit activity. After controlling for potential selection bias in TIF assignment, this paper shows that TIF ultimately fails the ‘but-for’ test and shows no evidence of increasing tangible economic development benefits for local residents.” (emphasis added)

In the paper, the author clarifies:

“To clarify these findings, this analysis does not indicate that no building activity or job crea-tion occurred in TIFed block groups, or resulted from TIF projects. Rather, the level of these activities was no faster than similar areas of the city which did not receive TIF assistance. It is in this aspect of the research design that we are able to conclude that the development seen in and around Chicago’s TIF districts would have likely occurred without the TIF subsidy. In other words, on the whole, Chicago’s TIF program fails the ‘but-for’ test.

Later on, for emphasis:

“While the findings of this paper are clear and decisive, it is important to comment here on their exact extent and external validity, and to discuss the limitations of this analysis. First, the findings do not indicate that overall employment growth in the City of Chicago was negative or flat during this period. Nor does this research design enable us to claim that any given TIF-funded project did not end up creating jobs. Rather, we conclude that on-average, across the whole city, TIF was unsuccessful in jumpstarting economic development activity — relative to what would have likely occurred otherwise.” (emphasis in original)

The author notes that these conclusions are specific to Chicago’s use of TIF, but should “should serve as a cautionary tale.”

The paper reinforces the problem of using tax revenue for private purposes, rather than for public benefit: “Essentially, Chicago’s extensive use of TIF can be interpreted as the siphoning off of public revenue for largely private-sector purposes. Although, TIF proponents argue that the public receives enhanced economic opportunity in the bargain, the findings of this paper show that the bargain is in fact no bargain at all.”

TIF is social engineering

TIF represents social engineering. By using it, city government has decided that it knows best where development should be directed. In particular, the Wichita city council has decided that Old Town and downtown development is on a superior moral plane to other development. Therefore, we all have to pay higher taxes to support this development. What is the basis for saying Old Town developers don’t have to pay for their infrastructure, but developers in other parts of the city must pay?

TIF doesn’t work

Does TIF work? It depends on what the meaning of “work” is.

If by working, do we mean does TIF induce development? If so, then TIF usually works. When the city authorizes a TIF project plan, something usually gets built or renovated. But this definition of “works” must be tempered by a few considerations.

Does TIF pay for itself?

First, is the project self-sustaining? That is, is the incremental property tax revenue sufficient to repay the TIF bonds? This has not been the case with all TIF projects in Wichita. The city has had to bail out two TIFs, one with a no-interest and low-interest loan that cost city taxpayers an estimated $1.2 million.

The verge of corruption

Second, does the use of TIF promote a civil society, or does it lead to cronyism? Randal O’Toole has written:

“TIF puts city officials on the verge of corruption, favoring some developers and property owners over others. TIF creates what economists call a moral hazard for developers. If you are a developer and your competitors are getting subsidies, you may simply fold your hands and wait until someone offers you a subsidy before you make any investments in new development. In many cities, TIF is a major source of government corruption, as city leaders hand tax dollars over to developers who then make campaign contributions to re-elect those leaders.”

We see this in Wichita, where the regular recipients of TIF benefits are also regular contributors to the political campaigns of those who are in a position to give them benefits. The corruption is not illegal, but it is real and harmful, and calls out for reform. See In Wichita, the need for campaign finance reform.

The effect of TIF on everyone

Third, what about the effect of TIF on everyone, that is, the entire city or region? Economists have studied this matter, and have concluded that in most cases, the effect is negative.

An example are economists Richard F. Dye and David F. Merriman, who have studied tax increment financing extensively. Their article Tax Increment Financing: A Tool for Local Economic Development states in its conclusion:

“TIF districts grow much faster than other areas in their host municipalities. TIF boosters or naive analysts might point to this as evidence of the success of tax increment financing, but they would be wrong. Observing high growth in an area targeted for development is unremarkable.”

So TIF districts are good for the favored development that receives the subsidy — not a surprising finding. What about the rest of the city? Continuing from the same study:

“If the use of tax increment financing stimulates economic development, there should be a positive relationship between TIF adoption and overall growth in municipalities. This did not occur. If, on the other hand, TIF merely moves capital around within a municipality, there should be no relationship between TIF adoption and growth. What we find, however, is a negative relationship. Municipalities that use TIF do worse.

We find evidence that the non-TIF areas of municipalities that use TIF grow no more rapidly, and perhaps more slowly, than similar municipalities that do not use TIF.” (emphasis added)

In a different paper (The Effects of Tax Increment Financing on Economic Development), the same economists wrote “We find clear and consistent evidence that municipalities that adopt TIF grow more slowly after adoption than those that do not. … These findings suggest that TIF trades off higher growth in the TIF district for lower growth elsewhere. This hypothesis is bolstered by other empirical findings.” (emphasis added)

The Wichita city council is concerned about creating jobs, and is easily swayed by the promises of developers that their establishments will create jobs. Paul F. Byrne of Washburn University has examined the effect of TIF on jobs. His recent report is Does Tax Increment Financing Deliver on Its Promise of Jobs? The Impact of Tax Increment Financing on Municipal Employment Growth, and in its abstract we find this conclusion regarding the impact of TIF on jobs:

“This article addresses the claim by examining the impact of TIF adoption on municipal employment growth in Illinois, looking for both general impact and impact specific to the type of development supported. Results find no general impact of TIF use on employment. However, findings suggest that TIF districts supporting industrial development may have a positive effect on municipal employment, whereas TIF districts supporting retail development have a negative effect on municipal employment. These results are consistent with industrial TIF districts capturing employment that would have otherwise occurred outside of the adopting municipality and retail TIF districts shifting employment within the municipality to more labor-efficient retailers within the TIF district.” (emphasis added)

These studies and others show that as a strategy for increasing the overall wellbeing of a city, TIF fails to deliver prosperity, and in fact, causes harm.