The City of Wichita plans to expand a special tax district.

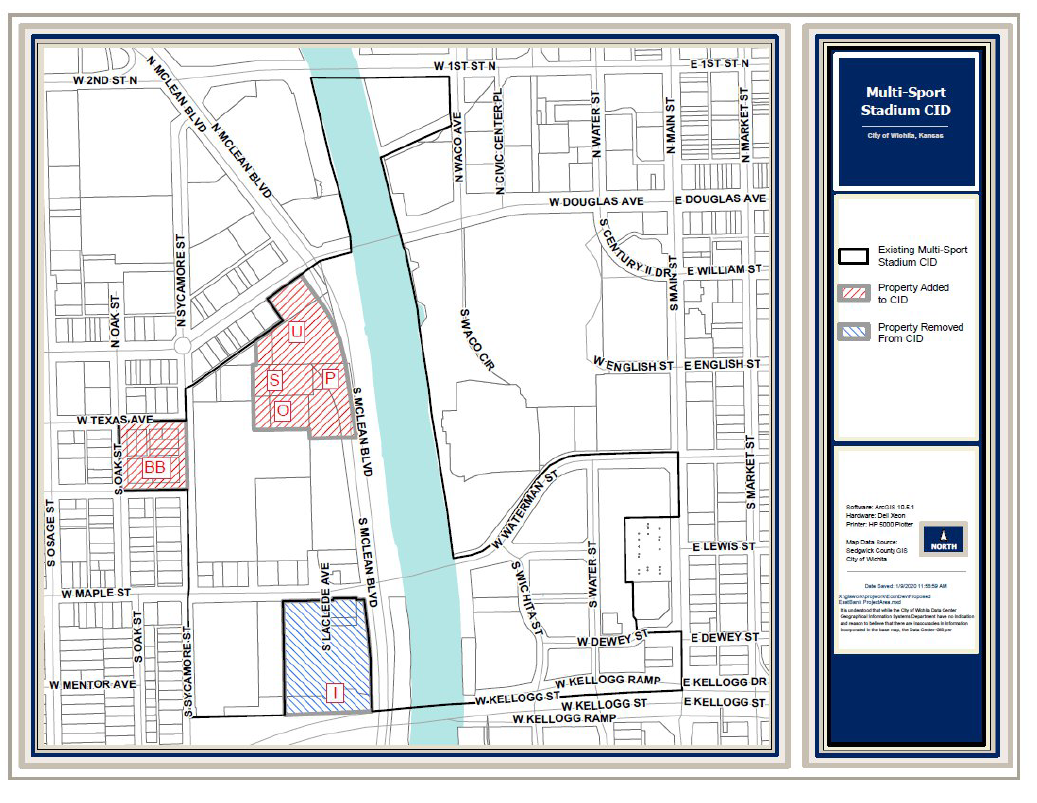

Next week the Wichita City Council will consider expanding an existing CID, or Community Improvement District, in the Delano neighborhood near downtown Wichita. A map provided by the city is nearby.

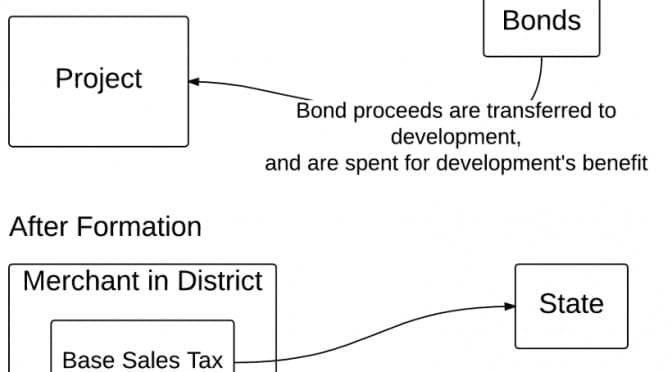

Community Improvement Districts are a mechanism whereby extra sales tax is collected within a district. For this CID, the city asks to collect an extra two cents per dollar, which is the maximum allowed in Kansas.

CIDs are distinguished from STAR bonds, in which incremental sales tax revenue in a district is captured and handled differently from the base sales tax. The sales tax rate remains as before. The ballpark and surrounding area use both CID and STAR bonds, as well as other public funding.

In its analysis appearing in the agenda packet for the February 11, 2020 meeting, the city provides this:

The expanded boundaries will permit the collection of additional CID revenues and the application thereof to development opportunities as well as the design and construction of the Stadium, utilities, parking, and other improvements related to the Stadium and river corridor improvements. The expansion further permits the use of funds to support the construction of public auditoriums and convention centers.

The CID petition included the $83,000,000 stadium project, which includes both the $75,000,000 stadium and $8,000,000 in supporting infrastructure. The amended petition has an estimated project costs of $210,200,000, which includes the additional $127,200,000 in project costs related to the Riverfront Partners project.

Project costs originally included costs related to the development of a multi-sport stadium, related infrastructure and adjacent commercial, retail residential and parking structures. The amendment has been expanded to include public auditoriums and convention centers as well as the additional commercial construction on the Development Site.

In this context, “Development Site” refers to the Riverfront Partners site north of the ballpark, southwest of Douglas and McClean Boulevard.

Of note, the CID includes a portion of the land included in the Riverfront Legacy Master Plan. The city contemplates that CID funds might be used there: “The petition also requests that the uses of CID revenues be expanded to include uses contemplated by the DA to be made on the Development Site, costs for additional parking and costs that may be associated with for potential development on the east side of the Arkansas River that is within the Stadium CID.”

The item the council will consider also includes a correction, as explained by the city: “The petition also requests removal of certain City-owned property that was inadvertently included in the Stadium CID.”

The city plans to borrow funds to be repaid by the CID tax collections: “The City anticipates issuing up to $13,000,000 in bonds, based on a pledge of CID revenue.”

Don’t want to pay? Don’t go there.

Does the use of CID mean the city has raised taxes? Certainly, the sales tax within the CID is higher (9.5 percent) than outside (7.5 percent). But that extra tax can be avoided. It is common for city council members to advise citizens that if they don’t want to pay the higher sales tax, just don’t go there.

On the surface, this reasoning is correct. But as explained in city documents, the city is borrowing money to be repaid by CID tax collections. If enough people take this advice and avoid patronizing merchants within the CID, there may be a shortfall of money to make bond payments. Since the city’s policy is that CID bonds are not backed by the full faith and credit of the city, Wichita as a city is not on the hook. 1 But should this happen and the city defaulted on CID bonds, it would be a severe blow to the city’s reputation.

A similar situation exists for the STAR bonds the city has issued to fund the ballpark and related spending. If the district fails to generate enough incremental sales tax revenue to make bond payments, city taxpayers are not liable. 2 But the failure of these bonds would, again, severely damage the city’s reputation.

Further, the city expects property tax revenue to pay off tax increment financing (TIF) bonds issued in favor of the project.

Even more, the city expects the economic activity generated by the ballpark and surrounding development to spin-off associated economic activity that will generate further tax revenue. If this does not happen, and happen in a big way, the project threatens to be a burden on the city budget, and by extension, taxpayers.

—

Notes

- City Of Wichita Community Improvement District Policy. “While the CID Act permits the issuance of either full-faith and credit general obligation bonds or special obligation bonds, payable solely from the CID revenue, it is the policy of the City of Wichita to issue only special obligation CID bonds.” ↩

- $42,140,000 City Of Wichita, Kansas Sales Tax Special Obligation Revenue Bonds (River District Stadium Star Bond Project) Series 2018. “The series 2018 bonds are not general obligations of the city and neither the full faith and credit nor the general taxing power of the city, the state, or any political subdivision thereof is pledged to the payment of the series 2018 bonds. The series 2018 bonds shall not constitute an indebtedness of the city, the state, or any political subdivision thereof within the meaning of any constitutional or statutory debt limitation or restriction.” ↩