Tag: Politics

-

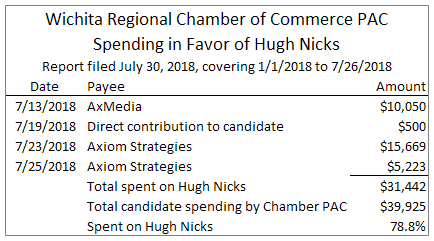

Wichita Chamber PAC spends heavily for Hugh Nicks

The Wichita Regional Chamber of Commerce PAC dedicates a large portion of its spending on placing its crony in office.

-

From Pachyderm: Candidates for Kansas House of Representatives

From the Wichita Pachyderm Club: Candidates for Kansas House of Representatives districts 74, 75, and 80. This was recorded on August 3, 2018.

-

Wichita Chamber PAC spending on Hugh Nicks

The Wichita Regional Chamber of Commerce PAC dedicates a large portion of its spending on placing its crony in office.

-

Hugh Nicks on character and respect in Sedgwick County

In the campaign for a Sedgwick County Commission position, character is an issue.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Author Bud Norman

In this episode of WichitaLiberty.TV: Journalist, author, and blogger Bud Norman joins Bob to discuss the local newspaper, Donald Trump, and the Kansas governor contest.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Kansas Gubernatorial Candidate Kris Kobach

Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach is a candidate for the Republican Party nomination for Kansas Governor. He joins Bob and Karl to make the case as to why he should be our next governor.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Larry Reed, Foundation for Economic Education

Lawrence W. Reed, President of Foundation for Economic Education, joins Bob and Karl to discuss the connection between liberty and character, our economic future, and I, Pencil.

-

Tuesday Topics: Money in Politics

A discussion on Citizens United and the influence of money in politics.

-

Wichita city council public agenda needs reform

Recent use of the Wichita City Council public agenda has highlighted the need for reform.

-

From Pachyderm: Can Wichita Elect a Governor?

From the Wichita Pachyderm Club: Dr. Russell Arben Fox, who is Professor of Political Science at Friends University. His topic was “Can Wichita Elect a Governor? Musings on the Kansas Political Landscape.”

-

NOTA a needed voting reform

“None of the Above” voting lets voters cast a meaningful vote, and that can start changing things.