Tag: Politics

-

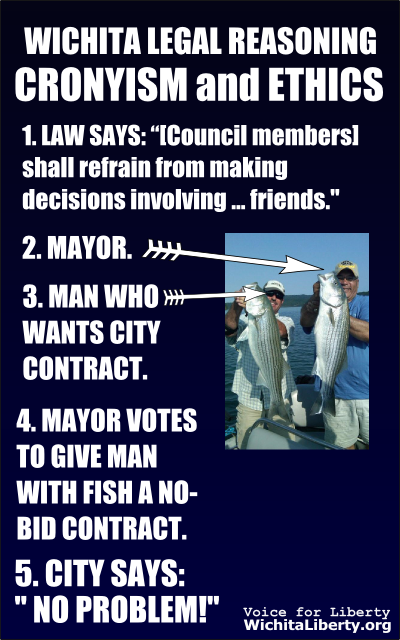

WichitaLiberty.TV: Water, waste, signs, gaps, economic development, jobs, cronyism, and water again.

A look at a variety of topics, including an upcoming educational event concerning water in Wichita, more wasteful spending by the city, yard signs during election season, problems with economic development and cronyism in Wichita, and water again.

-

Third annual Kansas Freedom Index released

The third annual Kansas Freedom Index takes a broad look at voting records and establishes how supportive state legislators are regarding economic freedom, student-focused education, limited government, and individual liberty.

-

For Tiahrt, earmarks are good government

Candidate for United States House of Representatives Todd Tiahrt defended the practice of earmarking federal spending.

-

Kansas political signs are okay, despite covenants

Kansas law overrides neighborhood covenants that prohibit political yard signs before elections.

-

Before asking for more taxes, Wichita city hall needs to earn trust

Before Wichita city hall asks its subjects for more tax revenue, it needs to regain the trust of Wichitans.

-

Arguments for and against term limits

The arguments in favor of term limits are presented, along with rebuttals to common objections to term limits.

-

Pyle, Kansas Senator, considering Roberts challenge

Could this be an effort by the Pat Roberts campaign to muddy the waters and diminish Milton Wolf’s prospects?

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Alternatives to raising taxes, how to become involved in politics, and bad behavior by elected officials

Wichita voters tell pollsters that they prefer alternatives to raising taxes. Then, how can you get involved in politics? A deadline is approaching soon. Finally, some examples of why we need to elect better people to office.

-

Voice for Liberty Radio: U.S. Rep. Mike Pompeo on Benghazi, Ukraine, and Boko Haram and the continuing threat of Islamic terrorism

United States Representative Mike Pompeo of Wichita has been appointed to the Select Committee on the Events Surrounding the 2012 Terrorist Attack in Benghazi. I spoke with him today in his Wichita office on this topic and a few others.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Examining surveys about the future of Wichita

In this episode of WichitaLiberty.TV: What do Wichitans want for their city’s future? Surveys from the City of Wichita and Kansas Policy Institute are examined.

-

ALEC should stand up to liberal pressure groups

Liberals can’t stand American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) because it is a strong and influential advocate for free market and limited government principals in state legislatures, and as a result are smearing it with unfounded charges of racism.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Newspaper editorial writers on how democracy works, Kansas school test scores.

An editorial in a Kansas newspaper exposes a dangerously uninformed and simplistic view of politics and democracy. Then, will Kansas school leaders and newspapers tell us the hidden truths about Kansas school test scores?