From Kansas Policy Institute.

School funding controversy is about entitlement, not need

By Dave Trabert

When every Johnson County school district qualifies as a property-poor district, you know you have a broken school funding formula … and a controversial claim based on entitlement.

The Kansas Legislature authorized $134 million in school funding this year in a good-faith effort to resolve the Supreme Court equity finding in Gannon v. State of Kansas. Most of the increase, $109 million –- was for Supplemental General State Aid (SGSA), which equalizes Local Option Budgets for property-poor districts. The other $25 million was for equalization of Capital Outlay aid.

The Legislature didn’t have to increase SGSA in order to satisfy the Supreme Court ruling on LOB equity, but they did so anyway. The $109 million authorized was based on calculations from the Kansas State Department of Education, but KSDE underestimated the amount by which districts would increase their Local Option Budgets, and now school districts want another $36 million from taxpayers. Districts want this money because the formula says they are entitled to it. But there is ample evidence that more money is not needed, and now SB 71 has been introduced into Senate Ways and Means Committee to revise the equalization formula and eliminate the $36 million increase.

SB 71 is opposed by school districts, but it is a necessary fix to a broken formula and frankly, districts don’t need the extra money.

The intention of SGSA is to offset wealth-based disparity among school districts, but calculations from the Kansas Department of Education has the current formula allocating $54.8 million to districts in Johnson County –- the state’s wealthiest county. Every district in Johnson County is considered a “property-poor” district under the current formula, including Blue Valley, which may be the most affluent district in Kansas.

Johnson County schools are being subsidized by taxpayers in far less affluent parts of Kansas under the current formula. One additional mill of property tax levied in the Blue Valley district raises $2.3 million; one mill raises $2.9 in Shawnee Mission and $1.7 million in Olathe. But taxpayers in counties where one mill generates less than $50,000 are being asked to subsidize property-rich districts; those counties include Cheyenne, Clark, Edwards, Ellis, Gove, Gray, Greeley, Kearny, Kiowa, Lane, Logan, Ness, Reno, Rice, Rooks, Rush, Russell, Stafford, Thomas, Trego and Wallace. One or more districts in those counties are considered ineligible for equalization aid by the current formula, but those districts’ patrons are expected to subsidize urban districts in Johnson County, Sedgwick County, Shawnee County and Wyandotte County –- just to name a few.

On the issue of need, the K-12 Commission on Student Achievement and Efficiency heard testimony from school districts, regional service centers and others recently, confirming that school districts could operate much more efficiently. However, school districts made it very clear that they are strongly opposed to being required to make efficient use of taxpayer money. Legislative Post Audit also told the Commission that districts have not enacted many of their recommendations to reduce the cost of services.

There is also no need to increase equalization of Capital Outlay aid. The $25 million allocated for this year was based on Capital Outlay property taxes levied by school districts last year, but districts increased local property taxes even more, entitling them to $20 million more in Capital Outlay equalization. This is another example of a broken school funding formula, as it has nothing to do with need. School districts began this year with a record $434.9 million set aside for Capital projects. Capital Outlay reserves are completely separate from capital projects related to bond issues and have increased each year since 2005. Districts may feel entitled to even more money for capital projects but there is no need to further pump up their reserves.

The equalization system and the entire entitlement-based school funding system need to be replaced with a student-focused and taxpayer-focused perspective.

“Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program.” — Nobel Laureate Milton Friedman

“Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program.” — Nobel Laureate Milton Friedman

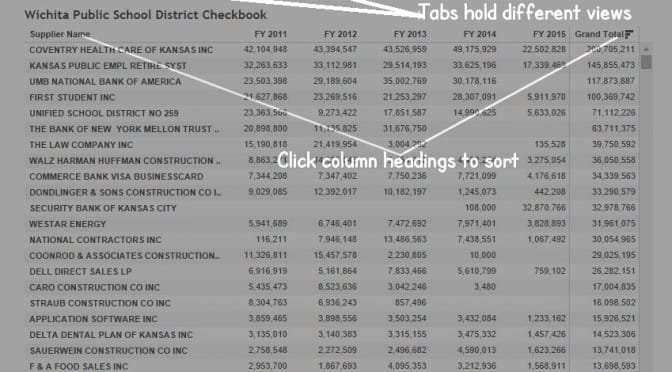

Data now available through November 2014.

Data now available through November 2014. There are some data quality issues, as seen nearby.

There are some data quality issues, as seen nearby.