Tag: Free trade

-

Donald J. Trump: “My Tariffs Have Brought America Back”

President Donald Trump argues that his sweeping tariffs have produced extraordinary economic growth, low inflation, booming investment, and enhanced national security, proving critics wrong.

-

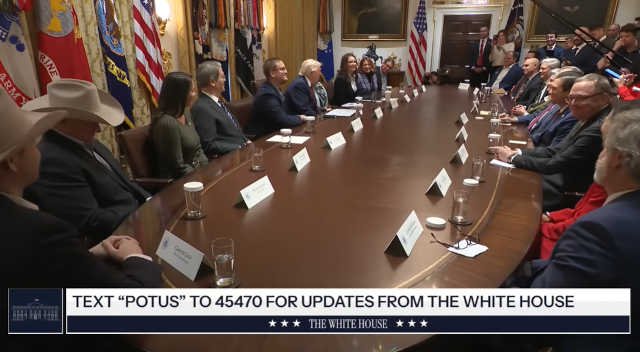

Roundtable: Trump Administration Announces $11 Billion Aid Package for American Farmers

President Trump unveiled an $11 billion farmer assistance package funded by tariff revenue, with $1 billion reserved for specialty crops. The December 8 roundtable featured major trade wins including over $40 billion in Chinese soybean purchases and $8 billion from Japan. Trump promised to remove environmental regulations on farm equipment to reduce costs.

-

Costco v. U.S. Customs and Border Protection: A Legal Challenge to Presidential Tariff Authority

Costco has filed a major lawsuit challenging President Trump’s 2025 tariffs as unconstitutional and unauthorized by law. This detailed legal analysis explains how the case tests whether the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) gives presidents authority to impose tariffs, or whether that power belongs exclusively to Congress. With two federal courts already ruling these…

-

Evaluation of “Trump Has The Power To Impose Tariffs Via IEEPA”

Peter Navarro argues that the International Emergency Economic Powers Act implicitly authorizes presidential tariffs because the power to “regulate importation” naturally includes tariffs, the traditional tool for controlling trade, and because presidents who can ban imports entirely should also be able to impose the lesser measure of taxing them. The article’s thesis is that IEEPA…

-

Supreme Court Hears Historic Arguments on Trump Tariffs: Can Presidents Tax Without Congress?

Can a president tax Americans without Congress? The Supreme Court just heard explosive arguments on Trump’s tariffs – with justices asking if a future president could declare a climate emergency to impose massive taxes. One justice called it a “one-way ratchet” where Congress would never get its constitutional power back. The stakes: trillions in trade…

-

The Employment and Wage Effects of Trump’s Steel Tariffs

Research on the Trump administration’s 2018-2020 steel tariffs reveals significant negative net employment effects despite modest gains in steel production jobs. While steel workers experienced some wage increases, the broader economic impact included substantial job losses in steel-using industries and higher costs for consumers.

-

Trump’s Tariffs Make Absolutely No Sense

Jason Furman argues that Donald Trump’s proposed “reciprocal tariffs” are based on flawed economic reasoning and would damage the U.S. economy, worsen global trade relations, and ultimately empower China.

-

It’s Time to End the Trump-Biden Trade War with China

This article discusses the ongoing trade tensions between the U.S. and China, which began during the Trump administration and continued under President Biden.

-

Tariffs, after all, are paid by Americans

Action taken in April by President Donald J. Trump confirms: The tariffs he imposed on China are paid by Americans.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Congressman Ron Estes

United States Representative Ron Estes discusses trade, FAA reauthorization and his amendment, entitlement reform, and spending.

-

Kansas benefits from foreign trade

The Kansas economy benefits greatly from foreign trade, and we should oppose restrictions on trade, writes Bryan Riley of Heritage Foundation.

-

Free trade is important, but may be in peril

Robert E. Litan, a lawyer and economist and adjunct senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations spoke on “The Future of Trade Policy” before a luncheon at the Wichita Pachyderm Club August 5, 2016.