Kansas school assessment standards remain at a high level, compared to other states. This is a welcome change from the past.

To evaluate the performance of their schools and students, states have their own assessments or tests. Some states have rigorous standards, meaning that to be considered “proficient,” students must perform at a high level.

But some states are less rigorous. They rate students “proficient” at a much lower level of performance.

How can we tell which states have high standards, and which states have low standards? There is a test that is the same in all states, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). The U.S. Department of Education, through the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), administers this test every other year. Known as “The Nation’s Report Card,” it is “the largest nationally representative and continuing assessment of what America’s students know and can do in various subject areas.” 1

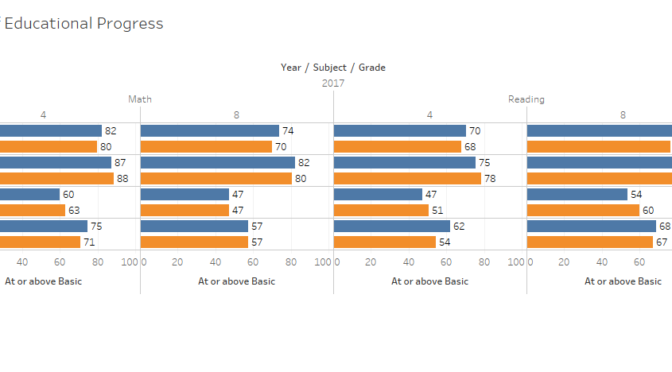

By comparing scores on NAEP and a state’s own tests, we can learn about the state’s standards. Does a state have a large percentage of students score “proficient” on its own test, but have a much lower percentage score “proficient” on the NAEP? If so, that state’s standards are weak.

After NAEP scores are released, Education Next, a project of the Program on Education Policy and Governance at Harvard University, compares state and NAEP results and assigns letter grades to each state. 2

It’s important to know that this analysis does not tell us how well a state’s students perform on any tests, either state tests or NAEP. Education Next emphasizes:

To be clear, high proficiency standards do not necessarily reflect high student performance. Rather, good grades suggest that states are setting a high proficiency bar — that students must perform at a high level to be deemed proficient in a given subject at their grade level. Grades gauge “truth in advertising” by indicating the degree to which states inform parents of how well their students are doing on an internationally accepted scale. 3

Kansas

The good news is that Kansas grades well in the analysis of its state proficiency standards for 2017, earning an overall grade of A (A in grade 4 math, B+ in grade 4 reading, and A in both grade 8 math and reading). This is the sixth highest score among the states and means Kansas assessments have a high degree of “truth in advertising.” These grades are nearly unchanged from 2015.

This high grade has not always been the case for Kansas, however. In 2013 the state received a grade of D+ and ranked forty-first. That was a little better than 2011, when the grade was D and rank was forth-forth.

Does this mean Kansas students are doing better on tests? No. NAEP scores are mostly unchanged, or changed very little. Instead, between 2013 and 2015 Kansas adopted more realistic and rigorous standards for its tests. It raised the bar for what students needed to know to be called “proficient.”

Here is an example of how low a bar Kansas once set: In 2009, 87.2 percent of Kansas students were judged “proficient” on state tests in grade 4 reading. But only 35.1 percent were judged “proficient” on the NAEP. For that year the average difference between “Kansas proficient” and “NAEP proficient” was 45 percentage points.

Despite this large difference, Kansans were being told the state’s schools are doing very well. In 2012, Kansas Commissioner of Education Diane M. DeBacker wrote this in the pages of The Wichita Eagle: “Kansans are proud of the quality of their public schools, and a steady and continuing increase in student performance over the past decade has given us ample reason for that pride.” (Diane DeBacker: Pride in Kansas public schools is well-placed, March 20, 2012.)

Bragging like this was common, and it was unfounded. It was a lie, and a harmful lie. Being told our schools are top quality based on state standards, when those standards are very weak, is politically expedient but untruthful, and the case for needed reform is dismissed as unnecessary.

—

Notes

- National Assessment of Educational Progress. About. Available at nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/about/. ↩

- “To generate these letter grades, we compare the percentage of students identified as proficient in reading and math on state assessments to the percentage of students so labeled on the more-rigorous NAEP. Administered by the U.S. Department of Education, NAEP is widely considered to have a high bar for proficiency in math and reading. Because representative samples of students in every state take the same set of examinations, NAEP provides a robust common metric for gauging student performance across the nation and for evaluating the strength of state-level measures of proficiency.”

Education Next. Have States Maintained High Expectations for Student Performance? Available at http://educationnext.org/have-states-maintained-high-expectations-student-performance-analysis-2017-proficiency-standards/. ↩ - Education Next. After Common Core, States Set Rigorous Standards. Summer 2016. Available at http://educationnext.org/after-common-core-states-set-rigorous-standards/. ↩