Tag: Interventionism

Friedman: Laws that do harm

As we approach another birthday of Milton Friedman, here’s his column from Newsweek in 1982 that explains that despite good intentions, the result of government intervention often harms those it is intended to help.

‘Love Gov’ humorous and revealing of government’s nature

A series of short videos from the Independent Institute entertains and teaches lessons at the same time.

The candlemakers’ petition

The arguments presented in the following essay by Frederic Bastiat, written in 1845, are still in use in city halls, county courthouses, school district boardrooms, state capitals, and probably most prominently, Washington

With tax exemptions, what message does Wichita send to existing landlords?

As the City of Wichita prepares to grant special tax status to another new industrial building, existing landlords must be wondering why they struggle to stay in business when city hall sets up subsidized competitors with new buildings and a large cost advantage.

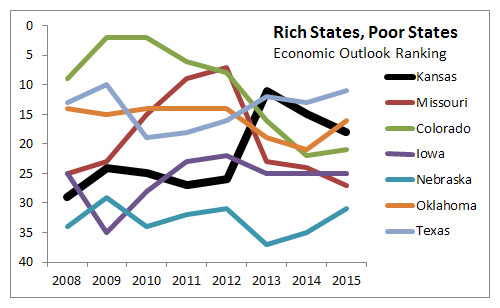

Rich States, Poor States, 2105 edition

In Rich States, Poor States, Kansas continues with middle-of-the-pack performance, and fell in the forward-looking forecast for the second year in a row.

In Kansas, PEAK has a leak

A Kansas economic development incentive program is pitched as being self-funded, but is probably a drain on the state treasure nonetheless.

Government intervention may produce unwanted incentives

A Kansas economic development incentive program has the potential to alter hiring practices for reasons not related to applicants’ job qualifications.

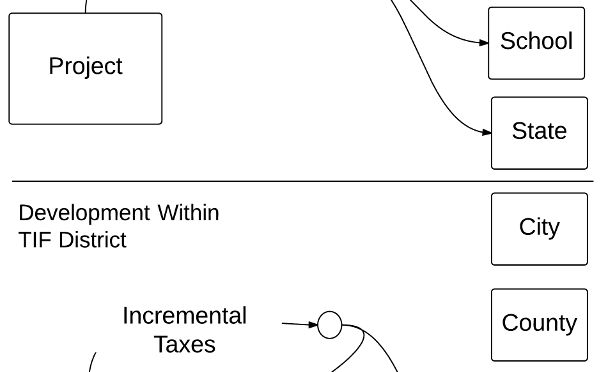

Wichita TIF projects: some background

Tax increment financing disrupts the usual flow of tax dollars, routing funds away from cash-strapped cities, counties, and schools back to the TIF-financed development. TIF creates distortions in the way cities develop, and researchers find that the use of TIF means lower economic growth.