Tag: Greater Wichita Economic Development Coalition

-

New metropolitan rankings regarding knowledge-based industries and entrepreneurship

New research provides insight into the Wichita metropolitan area economy and dynamism.

-

More Wichita planning on tap

We should be wary of government planning in general. But when those who have been managing and planning the foundering Wichita-area economy want to step up their management of resources, we risk compounding our problems.

-

In Wichita, respecting the people’s right to know

The City of Wichita says it values open and transparent government. But the city’s record in providing information and records to citizens is poor, and there hasn’t been much improvement.

-

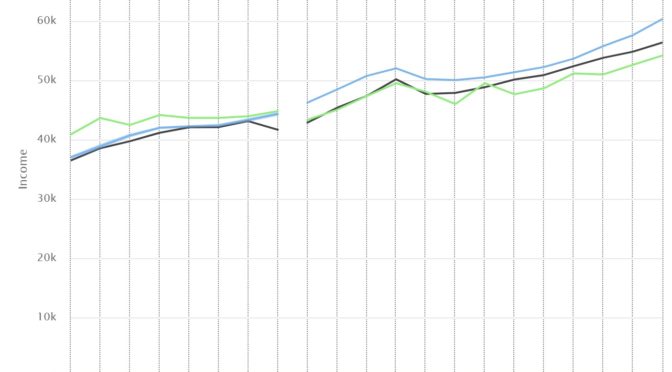

Sedgwick County income and poverty

Census data show Sedgwick County continues to fall behind the nation in two key measures.

-

An endorsement from the Wichita Chamber of Commerce

When the Wichita Regional Chamber of Commerce Political Action Committee endorses a candidate, consider what that means.

-

Wichita in ‘Best Cities for Jobs 2018’

Wichita continues to decline in economic vitality, compared to other areas.

-

Wichita employment down, year-over-year

At a time Wichita leaders promote forward momentum in the Wichita economy, year-over-year employment has fallen.

-

Wichita employment down, year-over-year

At a time Wichita leaders promote forward momentum in the Wichita economy, year-over-year employment has fallen.

-

Wichita job growth

Wichita economic development efforts viewed in context.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Wichita and Kansas economies

In this episode of WichitaLiberty.TV: Bob Weeks and Karl Peterjohn discuss issues regarding the Wichita and Kansas economies.

-

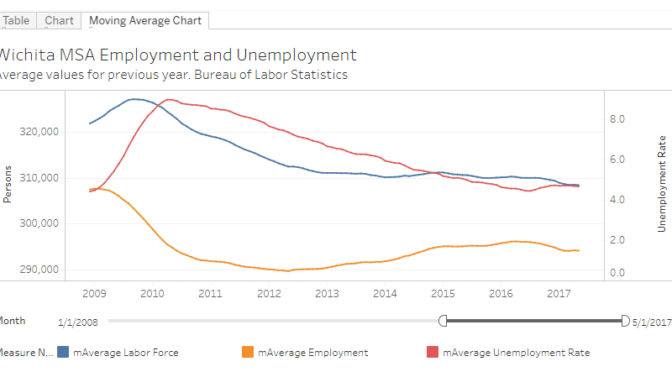

Wichita employment trends

While the unemployment rate in the Wichita metropolitan area has been declining, the numbers behind the decline are not encouraging.

-

Wichita MSA employment series

Charts of employment in the Wichita metro area, along with Kansas and the United States.