Wichita leaders want to diversify the area economy. Has there been progress?

In the wake of layoffs at Textron Aviation and Spirit Aerosystems, Wichita’s leaders shifted their attention to the need to diversify the Wichita metropolitan area economy. This has been a recognized need for a long time.

Recently the Wichita Eagle published an article addressing this matter. It did not, however, cite any statistics that measure the diversity — or lack of — in the Wichita economy.

One way to measure the concentration of an industry in a location is by the proportion of employment in that industry. The Bureau of Labor Statistics provides the number of employees by industry for metropolitan areas. I’ve gathered the data for the Wichita MSA for two industries: Aerospace Product and Parts Manufacturing (NAICS code 3364) and all manufacturing. I compare it to total private sector employment. This data is not adjusted for seasonality, as some are available only in that manner. Data is through June 2020.

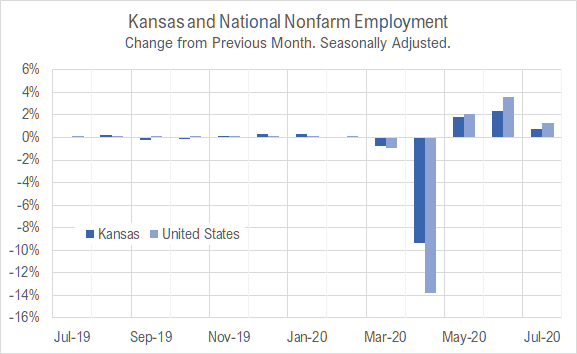

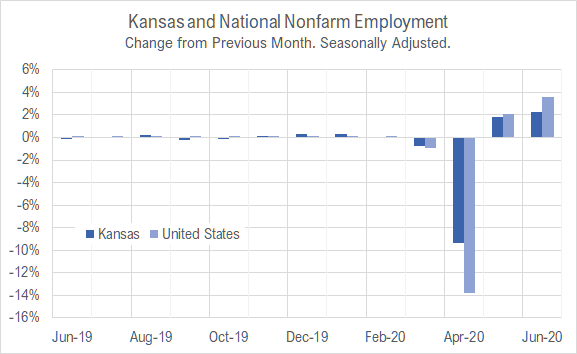

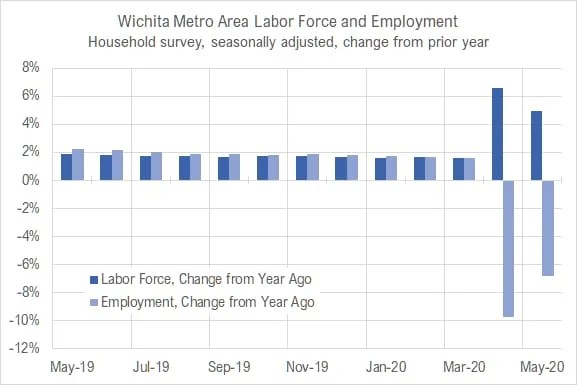

First, note the effects on employment due to the response to the pandemic.

Here are the employment ratios.

As the charts illustrate, there was a large downward shift in the two industry’s share of employment around the time of the Great Recession. Since then, the ratios have been more stable, with a slow decline until a small reversal of that trend over the last two years until the effects of the pandemic. That caused the ratios of employment in manufacturing to fall.

The charts of employment ratio changes from the same month one year ago confirms: Manufacturing and aerospace employment has grown faster than total private employment for the last two years or so, until the pandemic.

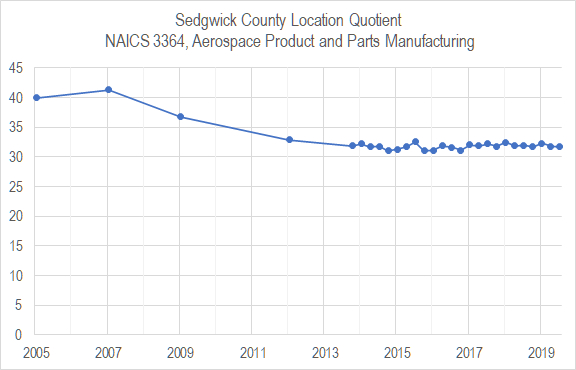

Another way to measure the concentration of industry is through location quotients. The Bureau of Labor Statistics provides these, most notably for counties as part of the Quarterly of Census and Wages. As described by BLS, “Location quotients are useful for studying the composition of jobs in an area relative to the average, or for finding areas that have high concentrations of jobs in certain occupations. As measured here, a location quotient shows the occupation’s share of an area’s employment relative to the national average.”

Further: “For example, a location quotient of 2.0 indicates that an occupation accounts for twice the share of employment in the area than it does nationally, and a location quotient of 0.5 indicates the area’s share of employment in the occupation is half the national share.”

This data is available by industry. I’ve gathered data for Aerospace Product and Parts Manufacturing (NAICS code 3364) for Sedgwick County and present it in a nearby chart. Data is through the end of 2019, and so does not reflect the pandemic.

First, note that the location quotient is large, averaging around 32 in recent years. This means the concentration of workers in this industry in Sedgwick County is 32 times the concentration nationwide.

Second, the location quotient fell from 2007 through 2014. Since then, it has been steady.

Has the Wichita area diversified its economy? Based on these two measures, the answer is yes. That increase in diversity coincided with a large decline in aviation-related employment, with that decline being larger than the decline in all Wichita-area private-sector employment. That was not planned or desired. It was a result of worldwide trends, most notably the Great Recession.

But since 2014, concentration in aviation-related employment has changed little, meaning no progress in diversification.

—

Notes