Tag: Education

-

Kansas City Star as critic, or apologist

An editorial in the Kansas City Star criticizes a Kansas free-market think tank.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Cost of Kansas schools, government schools, and understanding Kansas school outcomes

Is it true that some Kansas schoolchildren have no hope of attending a private school? What’s wrong with government schools? Then a talk on “Rethinking Education Tomorrow Starts with Understanding Outcomes Today.”

-

A Kansas school superintendent writes about school finance

A Kansas school superintendent explains school financing, but leaves out a large portion of the funds that flow to his district.

-

‘Game on’ makes excuses for Kansas public schools

Even if NAEP “proficient” is a lofty goal, it illustrates the shortcomings of Kansas public schools, especially for minority students.

-

A plea to a legislator regarding Kansas schools

On Facebook, a citizen makes an appeal to her cousin, who is a member of the Kansas Legislature.

-

They really are government schools

What’s wrong with the term “government schools?”

-

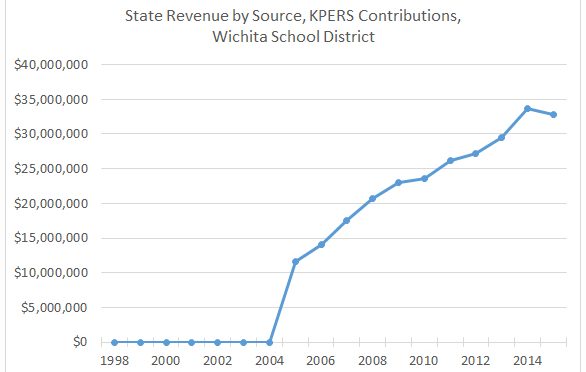

KPERS payments and Kansas schools

There is a claim that a recent change in the handling of KPERS payments falsely inflates school spending. The Kansas State Department of Education says otherwise.

-

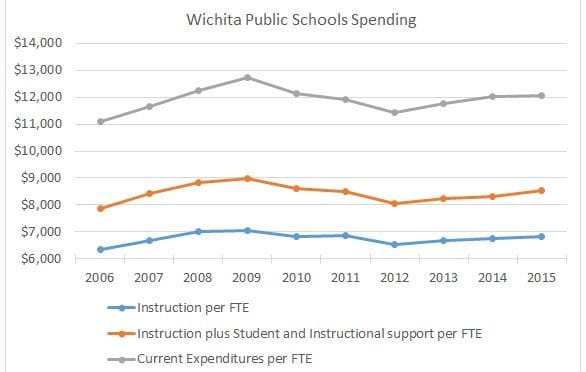

Wichita school spending

Spending by the Wichita public school district, adjusted for inflation and enrollment.

-

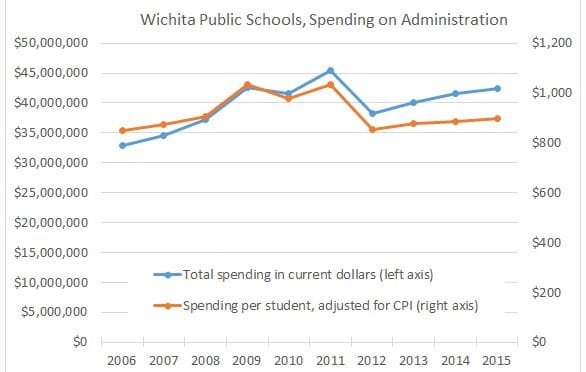

Wichita school district spending on administration

Could the Wichita public school district reduce spending on administration to previous levels?

-

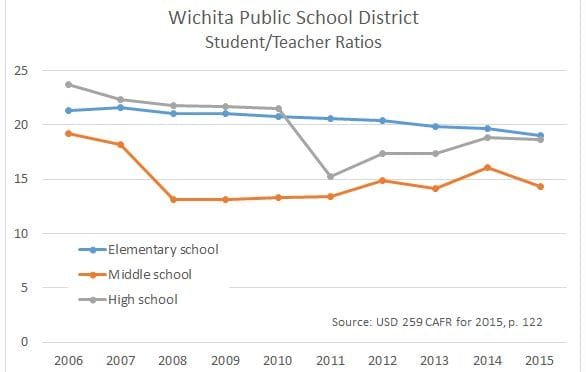

Wichita student/teacher ratios

Despite years of purported budget cuts, the Wichita public school district has been able to improve its student/teacher ratios.

-

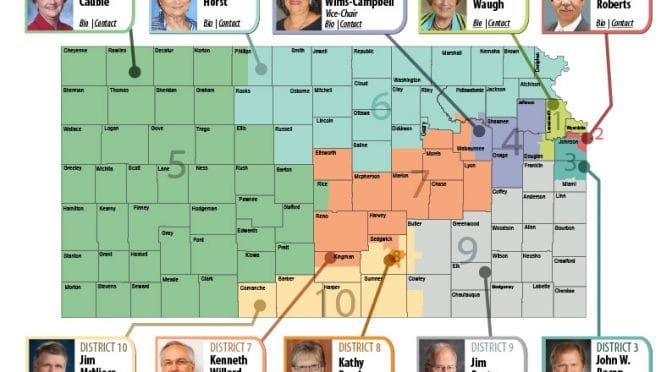

Kansas state school board member should practice what he preaches

A Kansas State School Board member urges political leaders to “tell the whole story” but doesn’t practice what he preaches, writes Dave Trabert of Kansas Policy Institute..

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: John Chisholm on entrepreneurship

In this episode of WichitaLiberty.TV: Author John Chisholm talks about entrepreneurship, regulation, economics, and education. View below, or click here to view at YouTube. Episode 119, broadcast May 8, 2016. Shownotes John Chisholm’s new book Unleash Your Inner Company: Use Passion and Perseverance to Build Your Ideal Business at Amazon and its own website. John…