Category: Kansas state government

-

Power of Kansas cities to take property may be expanded

A bill working its way through the Kansas Legislature will give cities additional means to seize property.

-

In Kansas, doctors may “learn” just by doing their jobs

A proposed bill in Kansas should make us question the rationale of continuing medical education requirements for physicians.

-

Kansas should adopt food sales tax amendment

A proposed constitutional amendment would reduce, then eliminate, the sales tax on food in Kansas.

-

Kansas highway spending

An op-ed by an advocate for more highway spending in Kansas needs context and correction.

-

Steve Rose and Jim Denning on the Kansas economy

Kansas City Star editorialist Steve Rose visits with Kansas State Senator Jim Denning.

-

Kansas transportation bonds economics worse than told

The economic details of a semi-secret sale of bonds by the State of Kansas are worse than what’s been reported.

-

This is why we must eliminate defined-benefit public pensions

Actions considered by the Kansas Legislature demonstrate — again — that governments are not capable of managing defined-benefit pension plans.

-

ACU rates the Kansas Legislature

The American Conservative Union has released its ratings for the 2015 Kansas Legislature.

-

Simple tasks for Kansas Legislature

In this excerpt from WichitaLiberty.TV: There are things simple and noncontroversial that the Kansas Legislature should do in its upcoming session.

-

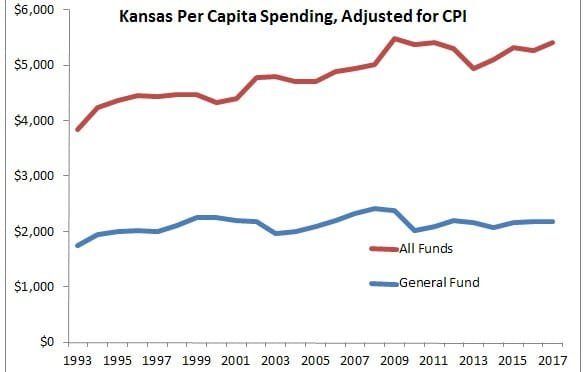

Spending and taxing in Kansas

Difficulty balancing the Kansas budget is different from, and has not caused, widespread spending cuts.

-

Kansas legislative resources, external

Besides the official Kansas Legislature resources, there are also these.

-

Kansas Attorney General Derek Schmidt

Kansas AG Derek Schmidt addressed cases in the Kansas and U.S. Supreme Courts in a talk at the Wichita Pachyderm Club.